Charlie O. Takes Charge

Enter Charlie O.

Part I — The Salesman Arrives

In December 1960, a 42-year-old insurance magnate from Indiana named Charles O. Finley bought the struggling Kansas City Athletics. He was brash, fast-talking, and, as one sportswriter later put it, “a salesman’s salesman.”

Finley had been chasing a big-league franchise since 1954, when he unsuccessfully bid against Arnold Johnson for the Philadelphia A’s. He later tried for the Detroit Tigers, Chicago White Sox, and even a proposed Los Angeles team, coming up empty each time. After years of chasing the dream, he finally had his ballclub.

But there was a catch: Finley had only been to Kansas City twice in his life. He admitted he’d never even seen Municipal Stadium. Until buying the A’s, he’d been a lifelong White Sox fan. Still, he insisted he’d win over the city — and fast.

“Kansas City is a gamble at the moment,” Finley told a reporter, “but most things in life are. If I had wanted to sell my soul for security, I would have stayed in the steel mills. I ventured out, and have not regretted it one day.”

Finley’s backstory sounded like a Horatio Alger novel. As a young man he’d worked in the steel mills of Gary, Indiana, before nearly dying of pneumonic tuberculosis — a two-year battle that left him flat on his back but ultimately pushed him to start his own insurance empire. By 1949, he had amassed a fortune estimated at more than $10 million.

“I love a challenge,” he said. “It was a challenge to whip my illness, to start this business, and now to build a ball club Kansas City can be proud of.”

Part II — The Show Begins

Finley spent most of January 1961 in Kansas City, meeting civic leaders and sports editors, promising to pour his energy and money into making the team a success. In the first few months, he bought out the 48-percent minority stake in the franchise to take full control — one of many rapid-fire moves meant to signal he was serious.

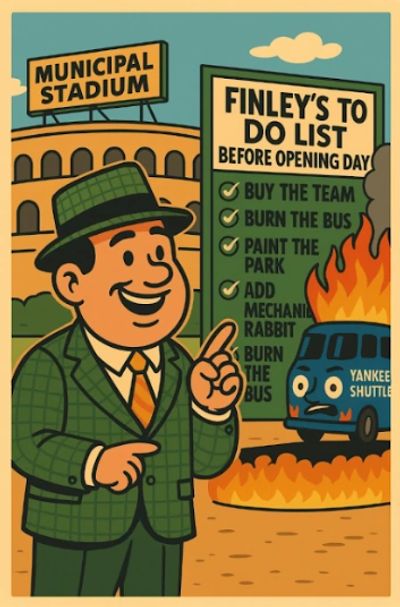

And when a reporter asked if he planned to continue the unofficial “Yankee shuttlebus” — the notorious pipeline that sent Kansas City’s best players to New York — Finley snapped:

“Well, you can tell them for me — the Yankee shuttlebus just doesn’t run anymore.”

To drive home the point, Finley staged one of the most unforgettable publicity stunts in baseball history. On a cold January afternoon at Municipal Stadium, he wheeled out an old school bus emblazoned with the words “Shuttle Bus to Yankee Stadium.”

Before a group of reporters, Finley set the bus on fire. Flames roared through the seats as smoke curled into the Kansas City sky. He stood beside the blaze, waving his hat triumphantly for the cameras.

The message was unmistakable: the days of the Athletics serving as a Yankee farm club were over.

Part III — The Circus at Municipal Stadium

Finley threw himself into Municipal Stadium like a man redecorating a dream house. The drab ballpark was repainted in bold turquoise and gold. A new picnic area sprouted beyond left field. And for Opening Day, Finley rolled out a circus of innovations that mixed engineering with pure showmanship.

There was “Little Blowhard,” an open pipe that rose from home plate to blow away dirt with compressed air — saving umpires from stooping to dust it off. A Fan-o-Gram, a giant electrical scoreboard near the auxiliary stands, could spell out messages in 50-foot-high letters. And then there was “Harvey,” a mechanical rabbit that popped up from a trapdoor near the plate to deliver baseballs to the umpire — eyes flashing, basket in paw, before retreating beneath the sod.

As fans entered Municipal Stadium for the first time in the Finley era, every corner of the park hummed with life. The Ruskin High School Golden Eagles band shared the field with the U.S. Army Reserve Airborne Division’s color guard, sharp in berets and white neck scarves, raising the flag in center field as “The Star-Spangled Banner” echoed through the stadium. Groups of musicians wandered the stands — some in cowboy hats, others in derbies or yellow caps — playing trombones and trumpets as the crowd of 25,000 settled in.

To top it off, Finley added theatrical flair even a circus might envy. During the opening fireworks display, tissue-paper animals inflated and floated away over the stadium, followed by sixteen aerial bombs that exploded simultaneously with a roar that shook the park.

And then came the roses — 10,000 hybrid tea roses imported from Florida, handed out to every woman in the crowd, varieties with names like Happiness, Christian Dior, and Jolie Madame.

Part IV — The Promise

Before the first pitch, Finley took the microphone to address the crowd. His voice quavered slightly as he thanked the fans for their faith and promised to bring them a championship team.

When he finished, fireworks burst overhead — and the crowd stood and roared. Finley tipped his A’s cap, tears running down his cheeks as the ovation continued. Moments later, he was back in his box seats, cheering wildly for every Kansas City hit, living and dying with each inning like a fan in the bleachers.

The A’s lost, 5–3, to the Cleveland Indians. But even the loss was drowned out by the carnival atmosphere — fireworks still bursting, the smell of roses still drifting through the stands.

“It was too bad,” Finley told reporters afterward, “but we’ll be back to give ’em hell tomorrow.”

For one gray, breezy afternoon, Municipal Stadium gleamed with new life and optimism. Finley promised Kansas City a winner within five years — “sooner if possible,” he said — and vowed to bring excitement back to the A’s.

In that moment, few doubted him. The years ahead would prove wilder than anyone could imagine — but on that April day in 1961, Charlie Finley had turned a tired franchise into a show, and Kansas City baseball had never felt more alive.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

We had our AI draw up a 60's cartoon to represent Charlie O.'s early days.

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.