The "Game of the Century"

A look at the 1933 All-Star game in Chicago.

The First All-Star Game: Baseball’s “Game of the Century”

Part I — The Birth of the Dream Game

By the summer of 1933, baseball needed a spark. The Great Depression had emptied wallets and grandstands alike. Attendance had cratered; the St. Louis Browns drew barely 80,000 fans all season — fewer than some modern weekend series. “Even with 25-cent baseball,” one Chicago columnist sighed, “the customers are not storming the gates.” Enter Arch Ward, the energetic sports editor of the Chicago Tribune. With the World’s Fair lighting up Chicago, Ward proposed a one-day “dream game” — a showcase of baseball’s biggest stars facing off purely for pride. He called it, with typical Chicago flair, “The Game of the Century.” Proceeds would go to charity: a relief fund for retired players and umpires struggling through the Depression.

White Sox manager Lew Fonseca praised it as a “game of triple purpose” — to revive interest, thrill visiting fans, and “provide real help for old players in distress.” Skeptics abounded. League officials said it was too complicated; managers fretted about injuries; purists dismissed it as a gimmick. But Ward persisted, recruiting AL president Will Harridge, Cubs owner William Veeck Sr., and securing Comiskey Park. The Tribune went all in — promoting the event, guaranteeing losses, and pledging profits to charity. Without Ward’s stubbornness, the game might never have happened.

The Tribune even organized the first-ever fan vote, running ballots through more than 50 newspapers nationwide. Long before stadium kiosks, fans mailed in their picks — baseball democracy by post. Still, not everyone was convinced. Syndicated columnist Joe Williams grumbled that the contest was “nothing more than a circus stunt set down in the atmosphere of a World’s Fair.” But by July 6, that “circus” had sold out. Forty-seven thousand fans filled Comiskey under hot summer skies. Grandstand seats cost $1.10 — a small fortune then — and every one was filled.

Part II — Ruth Steals the Show

They didn’t wait long for history. In the third inning, Babe Ruth, 38 but still the game’s main attraction, launched the first home run in All-Star history — a low line drive into the right-field stands. The Associated Press gushed: “Out of the shooting stars of baseball’s big dream game blazed the mighty war club of the one and only Babe Ruth.” As Ruth circled the bases, Eddie Collins danced in the third-base coach’s box, waving his cap like a kid. The crowd erupted.

There were light moments too. In the fifth, Lou Gehrig muffed a pop foul and drew friendly jeers from the Chicago crowd. Even in the “Game of the Century,” baseball stayed human. Connie Mack and John McGraw managed the teams — two icons from opposite eras, sharing one stage. McGraw, coaxed out of retirement, managed his final game that day. Not every star played: Mack benched Jimmie Foxx despite chants of “We want Foxx!” and Carl Hubbell rested after throwing an 18-inning complete game days earlier — the kind of workload that defined the era.

When it ended, the American League had won 4–2 on Ruth’s two RBIs. What could have been a stunt became a celebration — the birth of a summer tradition. Baseball had found its spark. And every time LeBron James dunks at All-Star Weekend or Connor McDavid dazzles in an NHL skills competition, they’re echoing that July afternoon at Comiskey Park in 1933 — the moment baseball invented the All-Star spectacle.

Part III — The AI Skipper’s Team of the Century

Arch Ward’s original Game of the Century was a showpiece for imagination — a way to dream up the greatest matchup ever played. But that was 1933, when the century was still young. Now, with the full 20th century in the books, we can look back and pick a true Team of the Century. Our experiment takes Ward’s idea one step further: what if that dream game were chosen not by memory or myth, but by a machine — no nostalgia, no bias, no heroes?

Enter our AI Skipper, tasked with building two 26-man rosters for the 20th century, one for each league, using a purely data-driven formula. No personality points. No deductions for scandal. No bonus for grace under pressure. The algorithm simply weighed performance and longevity to decide who made the cut — a cold, numerical echo of baseball’s century of greatness.

The result was a pair of flawless spreadsheets disguised as ballclubs: Bonds patrolling left field without controversy, Clemens striking out batters with no whispers attached, and Morgan edging out Robinson not for symbolism, but for OPS+ and WAR/162.

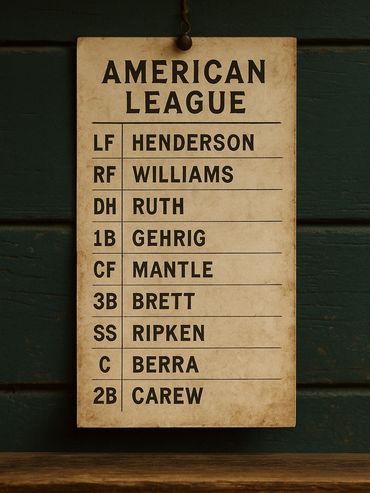

American League

Starting Lineup: Rickey Henderson (LF), Ted Williams (RF), Babe Ruth (DH), Lou Gehrig (1B), Mickey Mantle (CF), George Brett (3B), Cal Ripken Jr. (SS), Yogi Berra (C), Rod Carew (2B).

Rotation: Walter Johnson, Lefty Grove, Roger Clemens, Cy Young, Whitey Ford.

Backup Starters: Bob Feller, Jim Palmer, Pedro Martinez.

Relievers: Mariano Rivera, Dennis Eckersley, Rollie Fingers.

Bench: Joe DiMaggio, Carl Yastrzemski, Derek Jeter, Frank Robinson, Carlton Fisk.

Manager: Connie Mack.

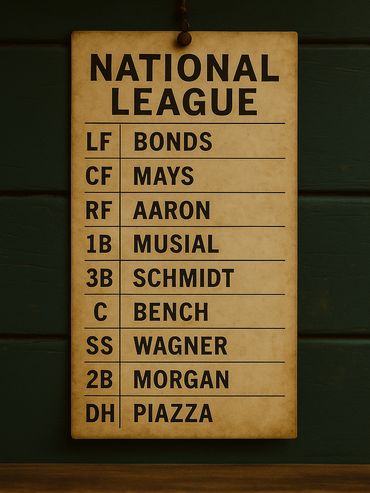

National League

Starting Lineup: Barry Bonds (LF), Willie Mays (CF), Hank Aaron (RF), Stan Musial (1B), Mike Schmidt (3B), Johnny Bench (C), Honus Wagner (SS), Joe Morgan (2B), Mike Piazza (DH).

Rotation: Sandy Koufax, Tom Seaver, Bob Gibson, Greg Maddux, Warren Spahn.

Backup Starters: Christy Mathewson, Steve Carlton, Don Drysdale.

Relievers: John Smoltz, Trevor Hoffman, Goose Gossage.

Bench: Jackie Robinson, Roberto Clemente, Willie McCovey, Pete Rose, Roy Campanella.

Manager: John McGraw.

Part IV — The Human Rebuttal

But baseball isn’t played by numbers. It’s played by people. And that’s where the Human Manager steps in — to remind the computer that greatness is more than a stat line.

Jackie Robinson vs. Joe Morgan: The AI is right that Morgan’s WAR and efficiency outpace Robinson’s shorter career. But Robinson didn’t just change a lineup; he changed a country. His courage under pressure, his Rookie of the Year and MVP awards in a segregated era — those belong to a different column of greatness, one the computer doesn’t keep. For this reason, Robinson might get the nod at second.

Roberto Clemente vs. Barry Bonds: Bonds’ numbers are undeniable — mountains of homers, oceans of walks, and a stat line built to break algorithms. But they’ll always come with an asterisk from the steroid era. Clemente’s greatness needed no such caveat: a man who died delivering aid to earthquake victims, whose arm, bat, and soul embodied baseball’s highest ideals. In the human version of the game, he replaces Bonds — even if it costs a few decimal points of WAR.

Roger Clemens and the Steroid Shadows: The AI doesn’t see PEDs; it only sees performance. But a human can’t ignore how the steroid era distorted the game’s record books. Maybe Clemens’ spot in the rotation goes to Bob Feller — who once traded Cy Young votes for a Navy uniform.

And that’s the beauty of the Game of the Century 2.0: both lists can be true. The AI captures achievement; the human restores meaning. Between them lies the full story of baseball — the science and the soul of the sport.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

The 1933 all-stars gather in Chicago.

Above Photos: The lineup cards that our AI Skipper wrote out for our own "Game of the Century" featuring its picks for the best players of the 20th Century.

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.