The Spitball Ban and the Science of Cheating

Gaylord Perry going through his spitball antics with the Mariners.

How Baseball Redrew the Line Between Gamesmanship and Crime

Part I: Cheating, Rule-Bending, and Baseball’s Ever-Changing Boundaries

Baseball has always lived in a gray zone between gamesmanship and outright cheating. The line between “clever” and “illegal” shifts with the era, the umpires, and whatever the rulebook happens to say that summer. The spitball was the perfect example — viewed by some as a legitimate pitch requiring real mastery, by others as a dangerous trick delivery born of foreign substances and deception.

The spitball debate echoed familiar tensions that appear whenever baseball redraws its boundaries: pitchers adapting to a livelier ball, hitters adjusting to a reinterpreted strike zone, managers wrestling with instant replay overturning decades of accepted “neighborhood plays,” or George Brett and the pinetar. Baseball has always had rules, and then the enforcement of rules — often two different things entirely.

By 1920 the sport was arguing not just about fairness, but safety. Ray Chapman had just been killed by a pitch from Carl Mays — a submarine pitcher, not a spitball artist — but the tragedy was quickly folded into a broader panic about “freak deliveries.” Soon the owners declared that all doctored-ball pitches would be eliminated after the 1920 season.

What made the decision so peculiar was that baseball did not actually ban the spitball outright. Instead, it created one of the strangest compromises in sports history: the pitch was illegal for all newcomers, but the existing spitballers were grandfathered in and allowed to keep throwing it for the rest of their careers. After 1920, a rookie was prohibited from using a pitch that half a dozen veterans were still permitted to throw.

For more than a decade, Burleigh Grimes, Stan Coveleski, and others performed under a completely different rulebook than the batters facing them. It was baseball’s version of having two strike zones on the same field. When Grimes threw the final legal spitball in 1934, the sport finally ended the era — but not before living for years with a rule that was both banned and not banned at the same time.

Part II: “Moist-Ball Artists,” Lost Livelihoods, and the Fight for Survival

The winter of 1920–21 became a referendum on fairness, safety, and economics. Spitballers had spent years perfecting a craft that was suddenly being classified as a menace, and the writers of the day made clear what was at stake.

Billy Evans, the American League umpire and occasional newspaper columnist, painted a vivid picture of how extreme ball-doctoring had become. Pitchers were cutting, scuffing, loading, rubbing, and greasing baseballs to such an extent that “most pitchers were forgetting there was such a thing as a curveball or fast one.” Batters lived in “constant danger,” fielders misplayed balls with unpredictable flight paths, and hitting averages were dropping in part from intimidation rather than skill. To Evans, eliminating the spitball and all “freak deliveries” was necessary for the health of the sport.

But even Evans argued — repeatedly — that existing spitball pitchers should be allowed to finish their careers. In one December 1920 column he warned that taking the pitch away immediately would destroy the usefulness of “sixteen pitchers of recognized major-league ability.” Their value would plummet overnight. Coveleski, he argued, would be a $50,000 pitcher with the spitball and merely ordinary without it. “It doesn’t seem quite fair,” Evans concluded.

Others were even more blunt. Brooklyn catcher Otto Miller, who had caught every game Burleigh Grimes pitched the previous season, called it “nothing short of robbing moist-ball artists of their means of livelihood.” Fans, he insisted, would not accept seeing Coveleski — fresh off dazzling them in the World Series — suddenly stripped of the delivery that made him great. “How would Cleveland fans accept a rule that meant the death of the moist delivery?” one columnist asked. “How would Tris Speaker feel about it?”

Then came Grimes himself, launching a full-throated defense. In an editorial he asked: “Why is a group of club owners allowed to take the spitball delivery from men who have spent ten to fifteen years of this short life to perfect it?” The safety argument had its champions, too — especially in the wake of Chapman’s death. One syndicated column noted grimly that many pitchers, whether spitballers or underhand throwers, “never have complete control of the ball.” The Chapman tragedy showed the cost of letting erratic deliveries proliferate.

But the loudest case for regulating the pitch wasn’t emotional — it was logical. The game had reached a point where pitchers themselves were joking, “Shall I pitch ’em wet, or shall I pitch ’em dry?” The fact that this was even a choice spoke volumes about how blurry the rules had become.

By the time the spitball faded into history, baseball had learned something more lasting than how to throw a dry ball. It had learned that every generation rewrites the rules of fairness to suit its own sense of balance. What seemed like outlaw trickery in 1920 would, decades later, be remembered as quaint ingenuity — and the same pattern would keep repeating. From corked bats to steroids to Spider Tack, the arguments barely changed, only the substances did. A century after Burleigh Grimes wiped the last legal spitball across his sleeve, the sport was still arguing about where gamesmanship ends and cheating begins.

Part III: The AI Spectrum of Cheating (and Why the Goalposts Keep Moving)

After sorting through a century of arguments — fairness, safety, gamesmanship, livelihoods — one thing becomes obvious: baseball has never agreed on what cheating is. What counts as savvy? What counts as dirty? And what counts as criminal?

A runner on second decoding signs? Smart baseball. A pitcher scraping a fingernail along the seams? Depends on the decade. Corked bats, pine tar, loaded balls, steroids, sign-stealing tech, Spider Tack — the moral line wobbles like a knuckleball.

So we asked our AI to rank common acts of rule-bending on a 1–100 scale — using 2025 sensibilities, not 1920’s or 2050’s. It produced a clean spectrum:

1–10: Traditional gamesmanship (sign-tipping from second, decoy tags, hidden-ball trick)

20–30: Borderline equipment tricks (slightly scuffed balls, discreet pine tar creep)

40–50: Classic illicit pitches (spitball, shine ball, emery ball)

55–65: Modern sticky-stuff enhancers (Spider Tack era)

70–80: Corked bats, illegal bat modifications

85–95: PEDs (steroids, HGH)

100: Tech-based, systemic cheating (Astros-style digital sign stealing)

Then there’s the one category that still sits above — or below — all the rest: gambling. Betting on games has always been baseball’s untouchable sin, a lifetime-ban offense that the sport treats as its moral Rubicon. Shoeless Joe Jackson’s alleged role in the 1919 Black Sox scandal and Pete Rose’s confirmed gambling on games as a manager remain the two great cautionary tales. Rose’s story took a final turn in 2025, when MLB posthumously removed him — and Jackson — from the permanently ineligible list after Rose’s death in 2024, making them technically eligible for future Hall of Fame consideration. But the historical record remains: both men were banned for betting on their own game, a crime baseball still ranks above steroids, sign-stealing, or any on-field deception. If the spitball was a 50 and steroids a 90, gambling is the permanent 110 — beyond forgiveness in life, and only tentatively forgiven in death.

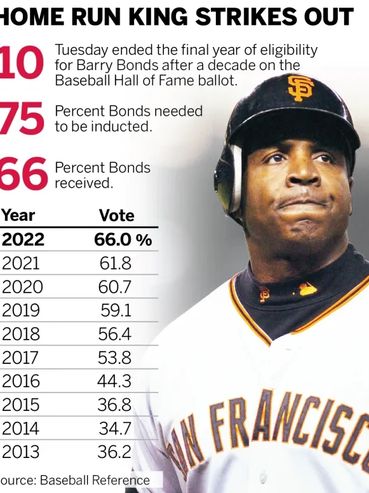

What’s striking isn’t the scale — it’s how many Hall of Famers sit across it. Gaylord Perry built a career in the 40–50 range. Ty Cobb almost certainly doctored spikes and balls — a 30–40 range act. Pitchers like Don Drysdale and Bob Gibson were legendary headhunters — behavior that might fall in a 60–70 “endangerment” tier today. Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Alex Rodriguez, and Manny Ramirez sit in the 85–95 band — all outside Cooperstown despite all-time numbers. David Ortiz, who appeared on an early, ambiguous PED list later dismissed by MLB, did get inducted. Pete Rose is an argument all to himself.

The spitball debate suddenly feels less like an antique curiosity and more like a mirror. Every era redraws the boundary. Every generation decides what counts as “too far.” In 1920 that meant a wet baseball. In 2025 it might be wearable biometric readers or AI-assisted pitch sequencing. In 2050 it may be something stranger still.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

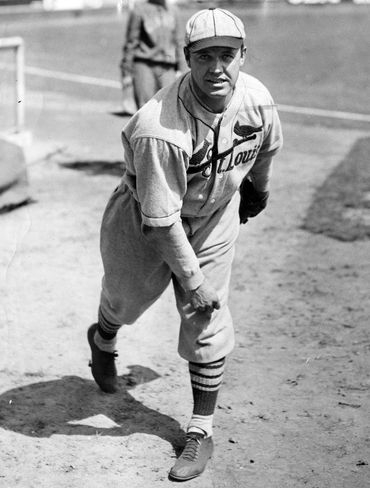

Burleigh Grimes applying his trade.

Cheating over the years: spitballers, Bonds, the Astros, Joe Niekro, and Sosa and his corked bat.

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.