The Prelude to the Merkle Boner

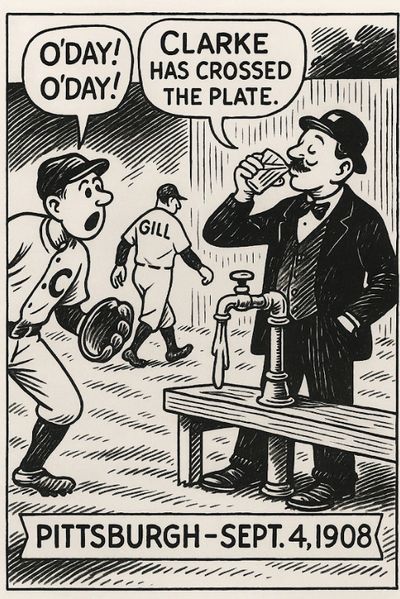

Our AI reimagined what a news cartoon of the Pittsburgh game might have looked like.

Setting the Stage

Part I — The Gill Game: A Sup of Water and a Spark of History

If you want to understand how Fred Merkle became baseball’s most famous scapegoat, you have to start three weeks earlier — not in New York, but in Pittsburgh. Because before the “Merkle Boner,” there was the “Gill Game.”

It was September 4, 1908, a hot Friday at Pittsburgh’s Exposition Park. The Cubs and Pirates were locked in a pennant race that had the whole National League sweating. The game had stretched into extra innings, and with the bases loaded in the tenth, Pittsburgh’s Owen Wilson lined a single to center. Fred Clarke scored from third. Pirates win, crowd erupts, game over.

Except… maybe not.

Warren Gill, the Pirates’ rookie first baseman, never actually touched second base. He’d run a few feet down the line, then turned toward the clubhouse, satisfied that the game was over. Sound familiar?

Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers had seen this movie before — or rather, was starring in its prequel. He grabbed the ball, stepped on second, and yelled for the umpire, Hank O’Day, to rule Gill out on a force. But O’Day wasn’t looking. The Pittsburgh Post described it perfectly:

“The instant the run was scored, Umpire Hank O’Day turned his back to the field and went to the hydrant for a sup of water.”

A sup, in 1908 slang — and one that changed baseball history.

Evers shouted, “O’Day! O’Day!” The umpire, thirst quenched and unmoved, gave one of the great deadpan lines in baseball history: “Clarke has crossed the plate.” Game over. Cubs furious.

That night, Chicago’s combustible owner, Charley Murphy, fired off a telegram to National League president Harry Pulliam, protesting the game. “Charley Murphy is getting peevish,” sniffed the Pittsburgh Press. Murphy argued that Gill had been forced out at second and that Clarke’s run shouldn’t count. He admitted he didn’t expect to win the protest but said he hoped it would make a case for hiring a second umpire: “Had there been another umpire on duty yesterday to look after the plays in the field,” Murphy said, “Gill would have been declared out and Clarke’s run would never have been allowed.”

The Pittsburgh Post agreed that it was a strange and instructive play: “It is a play that does not come often, but the next time it does happen, it is safe to predict that none who took part in yesterday’s game will overlook the importance of touching the next base ahead of them.”

They had no idea how right they were. Three weeks later, it happened again — almost line for line.

Part II — The Premonition Comes True

September 23, 1908, at the Polo Grounds in New York. Same stakes, same umpire, same team in the field. The Cubs were once again fighting for the pennant, this time against the Giants. Bottom of the ninth, score tied. The Giants’ Moose McCormick stood on third, rookie Fred Merkle on first. Al Bridwell singled to center, McCormick scored, and bedlam followed. Fans flooded the field, convinced the Giants had won.

But O’Day, the same umpire who had once gone to the hydrant for a sup of water, remembered Pittsburgh. He looked for the ball, saw Evers calling for it again, and this time, he ruled differently. The run didn’t count. Merkle had never touched second base. Game over — or rather, game not over. Officially declared a tie.

In that sense, the “Merkle Boner” wasn’t just a blunder — it was the delayed enforcement of a rule the Cubs had been arguing about for weeks. If anyone was set up that day, it wasn’t the Cubs; it was the Giants, and poor Fred Merkle most of all. He was a nineteen-year-old rookie, filling in for the ill Fred Tenney, and there’s almost no chance he knew about the earlier Gill play or Chicago’s protest. As far as he could tell, the crowd had decided the game was over — and back then, the crowd really did decide things sometimes.

Part III — The Forgotten First Act

Baseball history tends to love its morality plays: Buckner boots it, Snodgrass drops it, Merkle forgets to touch second. But the truth is usually messier — and in this case, more interesting. The Cubs didn’t stumble onto their protest by accident. They’d rehearsed it. They’d already lost one game on the same play and weren’t going to let it happen again.

If anything, the Merkle game was the league finally applying a rule it had already debated. The Cubs had made sure of that. The Post had even warned them all: “The next time it does happen, it is safe to predict that none who took part… will overlook the importance of touching the next base.” O’Day didn’t. Evers didn’t. But Merkle did — and he paid the price for everyone else’s education.

Part IV — The Long Shadow

The Gill game faded into obscurity, remembered only in the yellowing pages of the Pittsburgh papers, while Merkle’s name became shorthand for boneheaded blunders. That’s the way myths work in baseball — they simplify. They need one goat, not three weeks of rule confusion, telegrams, and umpire hydration breaks.

But once you know the prequel, the “Merkle Boner” looks different. It wasn’t just a mistake; it was a collision between two rulebooks — the one written down, and the one everyone thought they were playing by.

Part V — Epilogue

In 1908, three teams — the Cubs, Giants, and Pirates — finished within a single game of each other. The Cubs ultimately won the pennant after replaying the Merkle tie. But it’s not hard to imagine an alternate headline if Hank O’Day hadn’t learned his lesson in Pittsburgh. Maybe Chicago doesn’t protest. Maybe Merkle trots off the field in peace. Maybe Warren Gill is the name we all know today.

Instead, O’Day quenched his thirst, remembered his rulebook, and made Fred Merkle immortal.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

A bit of AI artistry: this painting reimagines a real 1908 photo of Fred Merkle leading off first.

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.