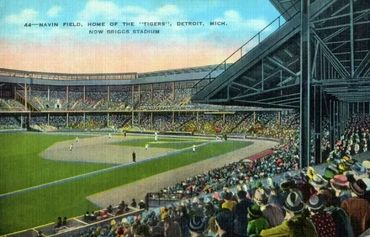

The Rumble at Navin Field

Part I: A Brawl Waiting to Happen

Before ballparks had luxury boxes and mascot races, they had fistfights. The grandstands were closer, the fences lower, and security extremely light. In the 1920s and ’30s, baseball was still shedding its rough-neck carnival roots — a time when an umpire might work with only one or two partners to police both the rulebook and a crowd of ten thousand half-buzzed spectators. Fans could and did stroll onto the field to argue a call. Players occasionally accepted the invitation to settle things “like men” beneath the grandstand after the final out.

And those crowds were mostly men — working-class, tobacco-chewing, paycheck-spending men who came to the ballpark to shout, drink, and, if necessary, swing. Beer was cheap, tempers shorter, and the line between participant and spectator blurry at best. Broken bottles littered outfield walls; fans heckled from spitting distance; teams sometimes needed police escorts to reach their trains. Fistfights were a fact of life in that era, as common in a barroom as at third base. The game reflected its times — rowdy, physical, and proud of it. It was baseball at its most thrilling, most human, and occasionally, most lawless.

Part II: The Riot at Navin Field

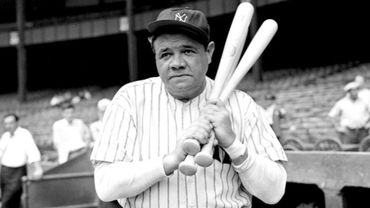

The trouble began, fittingly enough, with Babe Ruth throwing his weight around.

It was a sweltering Friday the 13th in June 1924, and the Yankees were pounding the Tigers at Navin Field, up 10–6 in the late innings. When Ruth, barreling down the first-base line in the seventh, “straight-armed” Detroit pitcher Bert Cole, tempers flared but the game went on — for a while. The Detroit Free Press would later write that “the fire smouldering since the time Ruth jostled Cole broke out in full blaze” two innings later, when Bob Meusel stepped to the plate and Cole hit him square in the back.

That was the spark. Meusel came storming toward the mound, and for a brief, tense moment it looked like he might reach Cole. But the Tiger left-hander, “perceiving the combative attitude of the big Yankee right fielder,” as the paper put it, “commenced to beat a masterly retreat.” The benches emptied as players, umpires, and fans poured onto the field, everyone shouting but no punches yet thrown.

The New York Times, covering the same game from the visiting dugout’s perspective, marveled at the bedlam: “The diamond was transformed into a shouting mob scene that no umpire’s voice could calm.” It was, the writer observed, one of those moments when “the crowd ceased to be spectators and became part of the contest.”

“Riots, fistfights, wholesale suspensions,” reported Free Press writer Harry Bullion, who watched the chaos spill from the diamond into the stands. A young, blond fan and a policeman — “either of whose pugilistic attainments would have made him a fortune in the prize ring,” Bullion quipped — began trading punches as the crowd pressed in.

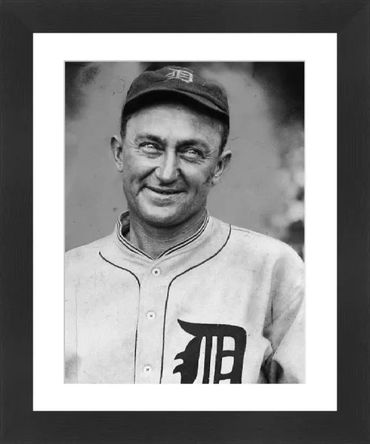

Only two umpires, Billy Evans and Brick Owens Ormsby, were working the game, and both were swallowed by the mob as they tried to restore order. Evans ejected players left and right, pleading for calm. Meanwhile, Meusel — still seething — retrieved his glove from right field and challenged Ty Cobb himself, Detroit’s fiery manager, even as Cobb was busy trying to disentangle Cole from the crowd surrounding him. Teammates finally dragged both men toward the dugouts.

After the game, the Yankees were livid. Ruth, Meusel, and Wally Pipp all claimed that Cole had been deliberately throwing at their heads. They even said they overheard Tiger infielder Heinie Basler mutter to Cole before Meusel’s at-bat, “If you must hit Bob, don’t hit him in the head.” Whether that conversation actually happened or not, it summed up the day — a blend of menace, mischief, and the casual violence that passed for gamesmanship in the 1920s.

The New York Daily News, meanwhile, described the scene differently. According to its reporter, Meusel “executed a few intricate steps and swung at Cole — he missed. Mr. Cole only smiled.” The paper said that as players and umpires converged, “Herman Ruth’s bulk was seen pushing its way through the throng. He was swinging his ham-like fists with abandon.” The Detroit and New York accounts couldn’t quite agree on who started what — but both agreed it looked more like a barroom than a ballgame.

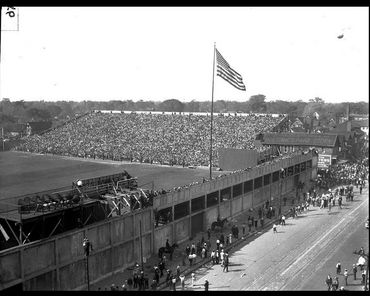

As the fight spilled toward the Detroit bench, thousands of fans vaulted the grandstand railing, milling toward the Tiger dugout and shouting for nothing short of murder of the Yankees. The infield was soon solidly packed, an “inadequate police detail” struggling to hold back the crush. The battling was, as one reporter wrote, “magnificent.” Even after the players were escorted off the field, more fights broke out, and thousands of spectators lingered on the diamond for half an hour after the game had been called. Bullion, no stranger to rough-and-tumble ball, called the whole episode “disgraceful conduct” — an insult, he wrote, to the intelligence of the baseball public.

When the dust settled, the Yankees had a 9–0 forfeit victory. The record book lists only the score, not the spectacle. Later, Ruth reportedly realizing that he’d been robbed of his glove, offered a $50 reward for its return — a small fortune in 1924.

In the days that followed, the league office handed down a few token suspensions and fines — the kind of after-the-fact discipline that did little to disguise the truth: on that Friday the 13th in Detroit, the game had simply outgrown anyone’s control.

Part III: The AI Blame-O-Meter — Who's to Blame for the Riot?

Ten thousand fans on the field. Two umpires swallowed by the mob. Babe Ruth throwing haymakers while Ty Cobb conducted the chaos like an angry symphony.

It got us wondering: who gets the blame for Detroit’s infamous Friday-the-13th riot of 1924? We fed the eyewitness accounts, box scores, and post-game quotes into the AI Blame-O-Meter, and asked it to assign percentage points of guilt for turning a summer ballgame into a street brawl.

Here's what we got back:

Ty Cobb (Manager, Tigers) — 32%

The master of mayhem. Known to needle pitchers into “message” pitches, Cobb’s fuse was as short as his temper was long. If anyone ordered the hit on Meusel, it was him.

Bert Cole (Pitcher, Tigers) — 15%

He threw the spark that lit the fire. Maybe acting on orders, maybe on instinct — either way, he aimed for drama and got a riot.

Bob Meusel (RF, Yankees) — 10%

Took one in the back and did what 1920s code demanded: charged. Hard to fault him for following the unwritten rule, but the charge made everything explode.

Babe Ruth (Sultan of Sparks) — 12%

His seventh-inning shoulder-check of Cole started the slow burn, and his ninth-inning entrance — “ham-like fists” swinging — turned smolder into inferno.

The Fans — 14%

Booze, bravado, and bad judgment in perfect harmony. Thousands poured from the stands, proving Detroit crowds didn’t need a wave to storm the field.

Lack of Security — 6%

Two umps, a handful of officers, and 10,000 restless men. Navin Field was one crossed word away from a stampede — and got it.

League Officials — 5%

For years the AL winked at beanballs and bench-clearing theatrics. The fines after this melee were pocket change; prevention wasn’t even policy.

Umpires Evans & Ormsby — 3%

Tried to part the Red Sea with a rulebook. They deserve hazard pay, not blame.

Ballpark Culture of the Era — 3%

Low fences, cheaper beer, and a national tolerance for brawling. In 1924, baseball and bar-fights were still first cousins.

The AI Blame-O-Meter delivers its verdict: Ty Cobb, 32% guilty, with honorable mentions to Ruth’s elbows and Detroit’s beer supply. The Tigers lost the game, the Yankees lost their gloves, and America gained a timeless reminder that baseball in the 1920s was one bad pitch away from turning into professional wrestling.

Part IV: The Human Perspective

The AI Blame-O-Meter may have pointed its digital finger at Cobb and company, but a human historian might see it differently. Arguably, the players were just doing what 1920s ballplayers did: chirping, posturing, and testing the limits of a game still half-barroom, half-ballet. No one actually threw a punch, and nothing they did was especially unusual for the era. What was unusual was that ten thousand fans were able to climb a low rail and join them.

In other words, this wasn’t a problem of personalities — it was a failure of structure. The real culprits sat higher up the chain.

Lack of Security & Stadium Design — 50%

Two umpires, a few cops, and little to keep the crowd at bay. That’s not a ballpark — that’s an invitation.

League Management — 40%

Decades of looking the other way on beanballs and brawls. No suspensions with teeth, no safety protocols, no sense of how close the sport was to chaos.

Everyone on the Field — 10%

Ruth, Cobb, Cole, Meusel — they just played the only game they knew. The environment made the riot, not the men.

When you view it that way, the riot becomes less a moral failure than a management one — proof that before baseball modernized, it was still learning the difference between crowd and mob.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

The Blame-O-Meter faults Ty Cobb for the Navin Field Rumble.

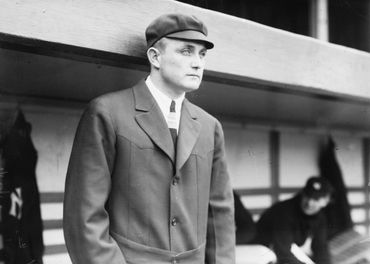

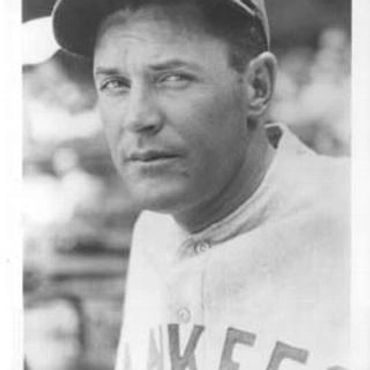

Shots of Navin Field, umpire Billy Evans, Yankee slugger Bob Meusel and Ruth and Cobb.

More From AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.