Gone Baby Gone: The Eephus Pitch

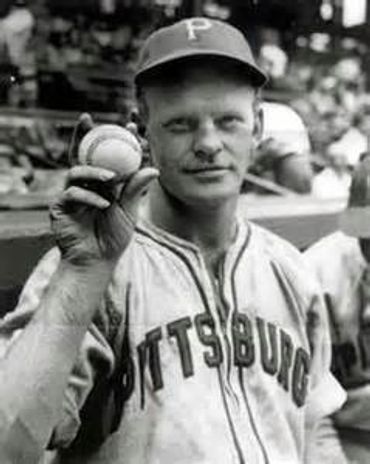

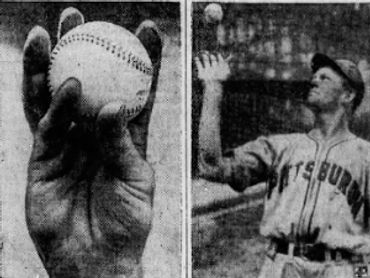

Rip Sewell gives up a home run to Ted Williams in the 1946 All-Star Game in Boston.

Gone Baby Gone: The Rise and Fall of the Eephus Pitch

Part I — The Pitch That Hung in the Air

They called it the Eephus — a pitch that seemed to hang in the air forever, a looping lob that made batters feel like they were waiting for rain. Pittsburgh Pirates right-hander Rip Sewell started fooling with it in 1942, just to see if he could make the ball drop straight into the strike zone. “One day Al Lopez asked me why I didn’t throw it in a game,” he said later. “I told him, ‘I think I will today.’” He did — and suddenly baseball had something new. Sewell won 20 games in both 1943 and 1944, mixing his normal stuff with this floating curiosity that climbed as high as 25 feet before plopping down through the zone.

Writers couldn’t even agree on what to call it — a blooper, a balloon ball, a butter ball, or simply “the nothing ball.” One paper marveled that it “parachutes down through the strike zone in a manner practically impossible to hit.” It was Sewell’s teammate Maurice Van Robays who gave it its name. When a reporter asked what “Eephus” meant, Van Robays shrugged: “Eephus ain’t nothing — and that’s what that pitch is. Nothing.”

After one game, Boston Globe sportswriter Jerry Nason quipped that the Braves “had eminent success practically any time Sewell pulled the rip-cord,” but even when hitters knocked him around, everyone left the park talking about the same thing — that floating pitch that seemed to defy gravity and logic alike.

Part II — The Phenomenon Takes Flight

By the spring of 1945, Rip Sewell had a full-blown phenomenon on his hands. He told reporters he’d “had a million laughs out of the way some of the fellows go after it.” Then he issued a challenge: “I’d like to see someone hit a homer off that pitch. I don’t think it can be done.” At that point, he claimed only Stan Musial had ever hit more than a single off it. The rest either popped it up or swung themselves dizzy. The Eephus had become half weapon, half sideshow — a slow-motion prank that made professionals look foolish and fans howl with delight.

By 1945, the Eephus was both Sewell’s calling card and a minor-league attraction all its own. Kids filled the stands at Forbes Field just to see it drop from the clouds. “The kids love it,” Sewell said. “I throw it and the batter takes a terrible swing. When he walks back to the dugout, the kids yell, ‘Sucker!’” He used it sparingly — just enough to rattle hitters — and he learned which ones to leave alone.

Part III — Ted Williams and the Ultimate Test

On July 9, 1946, one of baseball’s biggest stages gave the blooper its ultimate test. Sewell, now 39, faced Ted Williams in the first post-war All-Star Game at Fenway Park. The crowd of 34,000 leaned forward. Sewell, grinning, couldn’t resist. “I wanted to see how far he could hit it,” he said afterward. Williams could. The pitch floated high, then came tumbling down — and Williams launched it over the right-field bullpen. “Up and up and up it went,” wrote one reporter, “while traveling out and out and out.” Another said it looked like “a falling rock,” with Williams “backing up as if to dodge it.”

“It’s the first home run ever hit off the Eephus,” Sewell told reporters. Even the opposing bench was impressed. National League third baseman Whitey Kurowski told Williams it was “just about the greatest kick I’ve gotten out of baseball in a long time.” Sewell only smiled. “He’s the greatest hitter I’ve ever seen,” he said. “He just loves to bat. He doesn’t walk up to the plate — he runs up to it.” Then, with perfect calm: “It was a dead-ball game and I thought the fans might as well have a thrill."

Part IV — The Pitch That Wouldn’t Die

The Eephus didn’t disappear all at once — it drifted away, like the pitch itself. Satchel Paige toyed with a version on the barnstorming circuit, floating pitches so slow they made hitters laugh before he blew a fastball by them. Bill “Spaceman” Lee revived it three decades later as the “Leephus,” and in Game 7 of the 1975 World Series, he lobbed one to Tony Pérez, who crushed it for a two-run homer that flipped a 3–0 Boston lead into heartbreak and helped give the Reds the title.

From Sewell’s grin to Williams’ blast to Lee’s bravado, the Eephus traced one long, looping arc — from curiosity to comedy to folklore. In the end, it wasn’t lost so much as retired, drifting out of baseball like the pitch itself — slow, strange, and unforgettable.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

Look what our AI robot found discarded in the attic.

Above Photos: Rip Sewell showing his eephus grip and Ted Williams knocking the pitch into Fenway's right field bullpen. We also had the AI clean-up an AP cartoon of Rip pulling the rip-cord and Bill "Spaceman" Lee.

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.