The Brooklyn Dome

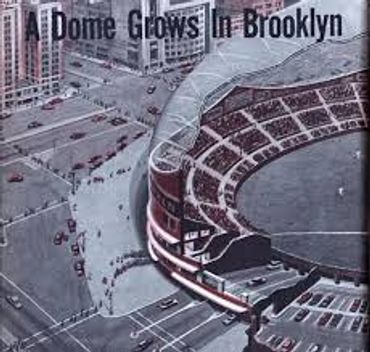

Our AI gave a little more personality to Walter O'Malley's plans for the dome in Brooklyn.

How Walter O’Malley’s 1950s dream nearly changed baseball forever

Part I — The Cathedral of Flatbush

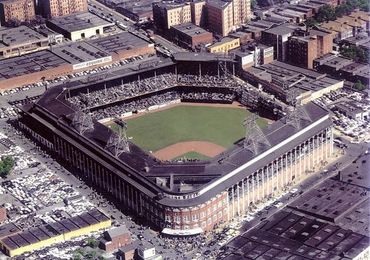

Of all the vanished cathedrals of baseball, none glows quite so warmly in memory as Ebbets Field. You can still picture it: the trolley clanging down Bedford Avenue, the Sym-Phony Band tooting in the stands, Abe Stark’s sign in right promising a free suit to anyone who could dent it with a line drive.

The place was imperfect — tight corners, bottlenecked rotunda, creaky seats — but it felt like home, a ballpark stitched right into the neighborhood’s rhythm.

And in 1955, when the “Bums” finally won it all, that patchwork charm turned sacred. For one glorious autumn, Brooklyn really did beat the world — or at least the Yankees. No wonder people still talk about Ebbets Field in the present tense. It was rickety, noisy, and utterly perfect.

Part II — The Businessman’s Dilemma

Despite their on-field success, the Dodgers’ box office never quite matched their legend. Through the early 1950s, they drew roughly a million fans a year — hardly embarrassing, but surprisingly middle-of-the-pack for a team that seemed to live in October and had just captured its long-awaited championship.

Ebbets Field was cozy and beloved, but also cramped, hard to reach, and impossible to park nearby. Meanwhile, Walter O’Malley watched the newly relocated Milwaukee Braves turn baseball economics upside down. After fleeing Boston in 1953, the Braves exploded from just a few hundred thousand fans to more than two million a year — the first team to truly harness the power of the automobile age. To a businessman like O’Malley, that was less a curiosity than a road map.

Part III — The Dream Dome

For all the grief Walter O’Malley has taken over the years, his Brooklyn plan shows he wasn’t simply looking to cash out and run. He could have jumped to Los Angeles as soon as the Braves proved westward expansion was a gold mine. Instead, he spent years fighting to stay put — proposing a modern, privately financed domed stadium that would have kept the Dodgers in Brooklyn for generations.

What he needed wasn’t public money, but public cooperation. New York master builder Robert Moses refused to budge, the city wouldn’t assemble the land, and eventually the West Coast’s open arms proved impossible to ignore. In hindsight, O’Malley’s “betrayal” looks more like the final act in a slow civic breakup — a borough clinging to nostalgia while progress moved out west.

This wasn’t some pipe dream scribbled on a cocktail napkin. O’Malley had real blueprints drawn up for a 55,000-seat domed stadium at Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues — a gleaming, all-weather ballpark designed by engineer Emil Praeger, complete with parking, subway access, and modern comforts Ebbets Field could never offer.

The roof would have been retractable, a marvel of mid-century optimism, and O’Malley even planned to pay for it himself. All he asked from the city was help securing the land — a maze of small warehouses and garages that only Robert Moses had the authority to clear. When Moses refused, the plan stalled, and Brooklyn’s future froze in place.

Part IV — The Irony of Progress

The irony is that O’Malley’s dream — had it come true — might have doomed the Dodgers to a different kind of purgatory. His proposed dome was the prototype for the multi-purpose “donut stadiums” that would soon blanket the country in the 1960s and ’70s: massive, symmetrical, and soulless.

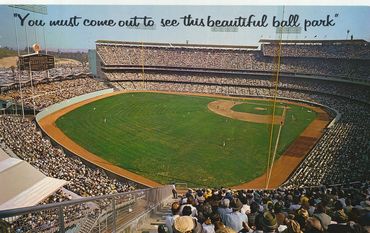

In escaping Brooklyn, the Dodgers accidentally escaped that fate too — landing instead in Dodger Stadium, one of the sport’s modern masterpieces.

And it’s worth remembering that in the 1950s, no one imagined a world where Ebbets Field could be lovingly renovated, its neighborhood revived, and its quirks preserved. That kind of nostalgia-driven urban renewal belonged to another era — one that, sadly, arrived just a little too late for Brooklyn.

Part V — The Simulation: If the Dome Had Been Built

We started to wonder: what would’ve happened if Walter O’Malley had actually gotten his Brooklyn dome? So we asked our AI machine to run the simulation. Its “predictions,” of course, are just educated guesses — the baseball equivalent of reading tea leaves in a box score — but here’s what it came up with:

- The Dodgers Stay Home

The Dodgers move into their gleaming space-age stadium around 1960. The Giants, left without a dance partner, head for Minneapolis, where they already have a farm club and a waiting ballpark. Washington keeps the Senators, and with no hole in New York’s National League lineup, there’s no outcry for a replacement team.

- Expansion, Not Migration

The West Coast still gets baseball — but through expansion instead of relocation. The American League makes the first move, placing teams in Los Angeles (the expansion Angels) and Houston, which takes the slot that historically went to Minnesota. The National League answers soon after, awarding franchises to San Francisco (perhaps reviving the old Seals name) and to either Dallas–Fort Worth or Denver.

- The Mets Never Happen

Queens likely still builds its municipal stadium around 1964, but without the Dodgers’ departure, there’s no emotional engine for the Mets — no Shea Stadium, no 1969 Miracle. By 1970, in this alternate universe, the Brooklyn Dodgers are still kings of Flatbush under their dome, the Minneapolis Giants rule the Upper Midwest, and California baseball has arrived right on schedule — just a few years later, by expansion rather than exile.

Part VI — Closing Reflection

O’Malley’s dome was never built, and Ebbets Field eventually fell — but for a fleeting moment, Brooklyn nearly became the center of baseball’s future instead of its past.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

Just for fun, our AI imagined Willie Mays on the "Minneapolis Giants." If Brooklyn stays, the Giants

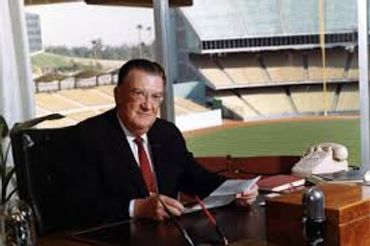

Photos of Walter O'Malley and the parks he considered. Ebbets Field, and especially the surrounding neighborhood, had seen better days by the mid-'50s. Although there were blueprints for a dome in Brooklyn, O'Malley eventually headed west for Chavez Ravine.

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.