Babe Ruth's World Series Gamble

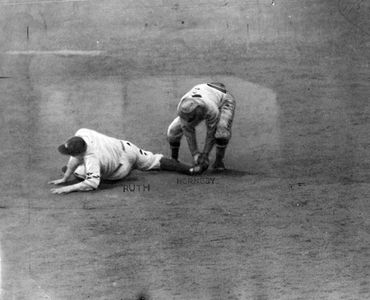

Babe Ruth is tagged out at second base by Rogers Hornsby in Game 7 of the 1926 World Series at Yankee Stadium — the play that ended it all (our AI lightly enhanced the original).

Babe Ruth’s Final Gamble in the 1926 World Series

Part I: The Play

Game Seven of the 1926 World Series. Yankee Stadium. Ninth inning. Two outs. The Yankees trailed the Cardinals, 3–2.

Babe Ruth had just worked a walk off Grover Cleveland Alexander — the old master who had famously come on in relief to strike out Tony Lazzeri with the bases loaded earlier. Standing at first, Ruth represented hope. At the plate was Bob Meusel, with Lou Gehrig waiting in the on-deck circle. And then, with everything on the line, Ruth took off for second base. Bob O’Farrell, the Cardinals’ catcher, fired a strike to Rogers Hornsby. Ruth slid in feet-first — and was tagged out. The Yankees’ rally died in Ruth’s dust, and the Cardinals were champions.

At the time, the play wasn’t instantly immortalized as the blunder we sometimes remember it as today. Contemporary newspapers were more dazzled by Ruth’s slugging than damning of his base running. He had swatted four home runs in the Series — an unprecedented power display in an era just shaking free of the dead-ball style.

The Associated Press even declared that Ruth and shortstop Tommy Thevenow were the “heroes” of the Series, while the Brooklyn Standard Union labeled Yankees shortstop Mark Koenig “the goat of the series” for his costly errors. In fact, the coverage leaned hard toward defending Ruth. Some later writers even floated the idea of a busted hit-and-run, a convenient way of shifting responsibility off the Babe.

But as the New York Times noted, Ruth was cut down by O’Farrell’s “deadly whip” of a throw, and the Boston Globe called O’Farrell “the world’s greatest baseball catcher.” It’s telling that, in the moment, the spotlight lingered on Ruth’s homers — not his final out. For the press of 1926, the Bambino was simply too large a figure to wear goat’s horns.

Part II: The AI Skipper’s Verdict

Modern analysis paints the play differently. We had our AI Skipper run a quick SABR experiment on whether the gamble made any statistical sense. Ruth stole bases at just a 50% success rate across the 1920s, a figure far too low to justify the risk. Sabermetric logic says a steal attempt only makes sense if the runner succeeds about 70–75% of the time. In 1926, Ruth had succeeded in 11 of 12 attempts, a sparkling 92% — but that was an outlier year. His career norms suggest the odds weren’t in his favor. And given the context — Meusel batting, Gehrig looming, the Yankees down a run — the expected value of Ruth’s gamble looks even shakier. Statistically, the smart play was to stay put.

Yet here’s the enduring paradox: the very audacity that made Ruth legendary at the plate also fueled this reckless dash. He lived on boldness, and sometimes boldness backfired. But the narrative never punished him much for it. Instead, history remembers his thunderous home runs, the awe of his swing, and his magnetic presence — not the desperate final slide that ended the 1926 World Series.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

The AI Skipper tells Ruth to stay at first base.

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.