Gone Baby Gone: The Player-Manager

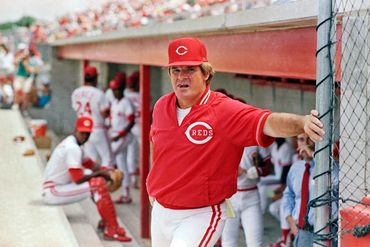

Pete Rose in his return to Cincinnati as the last player/manager in the big leagues.

The Rise, Fall, and Possible Return of the Player-Manager

Part I — When the Manager Wore Spikes

For most modern fans, the player-manager feels like a relic from a sepia-tinted baseball card — something belonging to the era of wool uniforms and train-car travel. But in baseball’s first half-century, the player-manager wasn’t an oddity. He was the norm.

The role evolved naturally from the team captain, a respected veteran who set lineups, organized drills, and handled clubhouse disputes while batting third and taking grounders every afternoon. Strategy was limited. Starters finished what they started. Bullpens were tiny. Most in-game choices were variations on the same two questions: bunt or don’t bunt? steal or stay put? Within that stripped-down environment, the player-manager thrived.

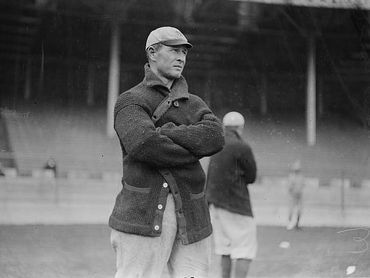

Frank Chance ran the early-1900s Cubs dynasty from first base. Tris Speaker managed the Cleveland Indians while patrolling center field. Even Connie Mack began as a catcher-manager before hanging up the gear for good. The model made intuitive sense: the smartest player — the team’s natural leader — happened to also be the manager. No one saw a conflict because the job wasn’t especially tactical; it was personal.

But the arrangement had weaknesses too. Superstars with prestige didn’t always have temperaments built for diplomacy or leadership. Ty Cobb, managing in Detroit, was famously volatile — his managerial stints were as fiery as his playing style. Rogers Hornsby was even harder to contain: brilliant hitter, impossible personality. He often took the manager’s job by default, only to alienate teammates and front offices until the roster was rearranged or he was traded again. The player-manager model was perfectly suited for leaders; it was a disaster for divas.

By the 1930s and ’40s, strategy was growing more complex. Relief pitching was slowly becoming a real profession. Scouting departments expanded. Opponents made platoons and matchups matter. And suddenly the idea of a man taking infield at 2:00 and diagramming bullpen leverage ladders at 7:00 no longer looked sustainable. The era of the player-manager was fading — but not gone.

Part II — The Boy Manager and the Hottest Seat in Baseball

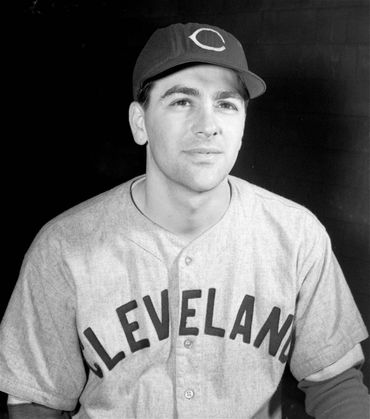

When Cleveland handed 24-year-old Lou Boudreau the dual title of shortstop and manager before the 1942 season, even friendly reporters admitted he’d been dropped into “the hottest seat in baseball.” Team president Alva Bradley promoted him partly out of admiration and partly out of a lack of better options — a young star suddenly asked to command older teammates and steer a roster in wartime flux. The announcement, made quietly in the League Park offices one November night, caught nearly everyone off guard. The Plain Dealer called it “a complete surprise,” even to insiders who assumed Bradley would never hand such responsibility to a 24-year-old.

Columnist Franklin Lewis of the Cleveland Press couldn’t resist the drama. “Take a powder, Horatio Alger — youse is strictly a bum,” he opened. To Lewis, Boudreau was the new American fable — a kid barely two years removed from the University of Illinois now running a million-dollar ballclub. “The kid can do the job,” he assured readers, “if he’s given a free hand by the tribal brass.” Lewis predicted “the Joes and Josephines” — Cleveland’s everyday fans — would rally behind the neophyte skipper and give him “the extra edge in public opinion a rookie manager needs.” They did, and six years later those same Joes and Josephines would save his job when Bill Veeck nearly replaced him.

Even at home, disbelief reigned. “I thought he was too young for the job,” said Mrs. Lou Boudreau from their house in Champaign, Illinois. “It all happened so fast … I just can’t believe it.” Boudreau had been coaching basketball at Illinois when the call came. He caught a train north and signed his contract that night. Bradley later admitted he’d interviewed a dozen other candidates but found most “disqualified by their personal or professional record.” What he wanted, he said, was a man whose private life was as spotless as his play — and Boudreau, calm, clean-cut, and admired by teammates, fit perfectly.

The new manager didn’t drink or smoke, and his language was as polite as his double plays were sharp. But on the field he could burn hot. Reporters recalled the time he had to be restrained from swinging at a St. Louis Browns infielder who’d spiked his 200-pound teammate Ray Mack. Boudreau weighed 160. That mix — measured off the field, fiery on it — was precisely what made him compelling: the kid skipper with a clean collar and a fighter’s spark.

Outgoing manager Roger Peckinpaugh offered a realist’s warning. “There’ll be times when he’ll boot one at shortstop and then have to take the pitcher out, and some fans will holler, ‘Why don’t ya take yourself out, ya bum?’ But if Boudreau can’t take that — and worse — and keep his chin up, he is worthy of the job.” He also cautioned, “He’s the boss now.” The rookie skipper would have to bench or even release friends he’d just shared trains and card games with. It was, Peckinpaugh said, “a tough assignment for any man — a tougher assignment for a boy.”

At his first press conference, the Plain Dealer’s Gordon Cobbledick noted that “Boudreau will be no rubber stamp.” Lou laid out his philosophy bluntly: “I want ballplayers who will eat, drink, and sleep baseball — and if I find we’ve got some of the other kind, I’ll get rid of them.” He also imagined a clubhouse where players could linger and talk baseball for hours — a true meeting place rather than a drab dressing room. Even at 24, he was thinking like both player and architect — half shortstop, half culture-builder.

But he knew the limits of the dual role. “I want a man I can depend upon to see things that I miss,” he admitted — a quiet nod to the fact that a player-manager couldn’t watch every strategic detail from the infield. By the 1940s, strategy had grown too intricate for one person to handle from shortstop; many relied on trusted bench coaches to track what they couldn’t see in real time. Boudreau’s remark captured that turning point: a job evolving faster than anyone could field it.

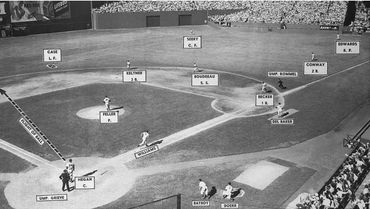

That March in Clearwater, one amused reporter noted that after a 9–4 spring loss, Boudreau “didn’t run off and leap into the Gulf of Mexico, which is just across the street from the ballpark.” The next morning, the “Boy Manager” was still there, trying again — a small triumph for a rookie skipper whose learning curve stretched from the infield dirt to the front office. Through those early years, Boudreau endured every variety of second-guessing but matured quickly. Even as ownership changed hands, he grew into the job: steady, diplomatic, quietly innovative. In 1946, new owner Bill Veeck nearly replaced him, but Cleveland fans voted with their hearts, and Veeck relented. Boudreau repaid that faith by guiding the club to the 1948 World Series championship — and by unveiling one of baseball’s most famous tactical experiments, the Ted Williams shift. It worked, sealing his legacy as the clean-cut prodigy who mastered both sides of the chalk line.

Pete Rose, who revived the player-manager model in the mid-1980s, showed just how far the job had drifted from those early days. By then the role had become too complex. Bullpens were deep. Matchups were microscopic. Media scrutiny was relentless. Rose excelled at motivating players but struggled with the tactical workload, and he eventually collided with the off-field scandal that would define him far more than his dugout decisions. His stint wasn’t a continuation of the Boudreau tradition — it was the last ember glowing at the edge of a dying fire.

Part III — The AI Crystal Ball and the Future of the Player-Manager

If anything signals that baseball history loops rather than marches, it’s what’s happening now. The rise of analytics, front-office modeling, and AI-based decision tools has quietly removed large swaths of tactical responsibility from the manager’s shoulders. Lineups, pitching plans, platoons, defensive alignments, even bullpen sequencing increasingly come from the analysts upstairs or from algorithmic projections, turning dugouts into the last stop on a long chain of pre-game decisions.

The old book said, “You don’t bat your best power hitter second.” The new book — written by data — says, “Yes, actually, you do.” Either way, the manager has always been judged for ignoring The Book. What’s changing is who writes that book and how much freedom the person in the top-step jacket really has. The job that once belonged to grizzled lifers with a gut feel now belongs as much to the laptops behind them.

What’s fascinating is where this could lead. If AI and front offices handle more and more of the strategic load, the manager’s job begins to resemble the 1900s again: manage personalities, set tone, motivate, communicate, keep the clubhouse aligned. Those were the very skills that made player-managers thrive in the first place — the ability to command a room, defuse tension, and pull 26 different egos in the same direction while still taking the field every night.

So our AI Crystal Ball peers ahead to 2070 and offers a scenario that feels strangely full-circle: the team splits the role. One uniformed “captain-manager” runs the clubhouse, communicates on the field, handles media, and becomes the emotional center of the roster. One analyst-manager — part strategist, part developer — handles the in-game decision matrix using a constellation of AI tools, match-up models, and real-time data feeds. Together they recreate the old dynamic: a leader on the field, a thinker off it, working in tandem instead of in one overburdened head.

It wouldn’t be a return of the 1920s player-manager, when one man scribbled the lineup and then trotted out to shortstop. It would be a hybrid — a modern remix of a very old idea, shaped by algorithms instead of scorecards. And Boudreau, standing at shortstop in 1948 calling his own defensive shifts, suddenly looks less like the last of something and more like the first glimpse of something baseball hasn’t quite invented yet.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

The Player-Manager has been shelved in the attic — at least for now.

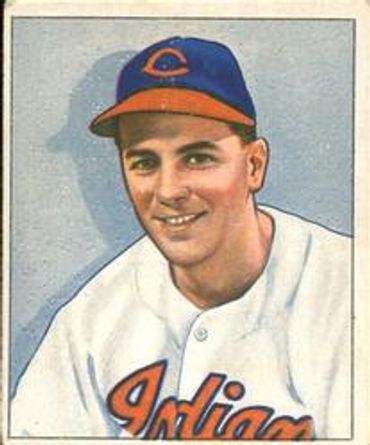

Player-managers over the years including the "boy manager," Lou Boudreau, Ty Cobb (speaking with Frank Navin), Frank Chance in an old-time sweater, and Pete Rose before the scandal. Boudreau's famous Williams shift is also documented above.

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.