Wartime Baseball’s Unlikely Trio

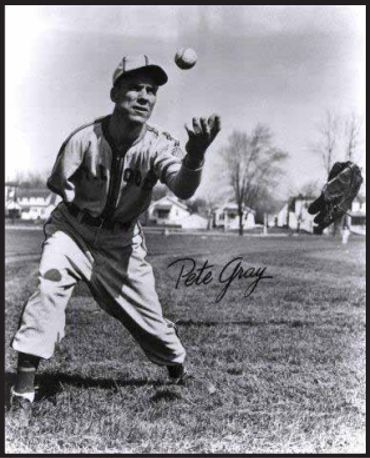

Pete Gray in action in 1945. (courtesy Public Domain Footage)

Part I: Wartime Baseball and the Green Light Letter

When World War II swallowed up the nation’s attention — and its ballplayers — there was real doubt about whether Major League Baseball should continue at all. Stars were vanishing into military service at a dizzying rate. By 1945, more than 500 major leaguers were in uniform, including Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Bob Feller, and Hank Greenberg. Teams filled the gaps with teenagers, aging veterans, part-timers, and men who in peacetime would never have reached the big leagues. But from Washington came a clear signal: keep playing.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “baseball’s No. 1 fan,” answered Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis’s question with the now-famous Green Light Letter of January 1942. Baseball, he wrote, was necessary wartime morale — a slice of normalcy for workers, soldiers on leave, and families living with daily uncertainty. Newspapers captured the question marks hanging over Opening Day of 1945. One columnist noted that after horse racing was “stopped cold, you wouldn’t have bet a thin dime” that Major League Baseball would manage to click into action that summer — but click it did, surviving on hope, habit, and Roosevelt’s blessing. For the clubs, the financial incentive was real; for the country, the emotional incentive was stronger.

So the majors kept going. The talent level dipped, the rosters warped, and the standings became unpredictable, but the game survived. And in that strange, makeshift ecosystem, a handful of unforgettable stories emerged — players who never would have reached the majors in peacetime suddenly stepping into the spotlight. One of the most remarkable was a one-armed outfielder from Pennsylvania coal country who spent his life proving he didn’t belong on anyone’s list of exceptions.

Part II: Pete Gray’s First Game

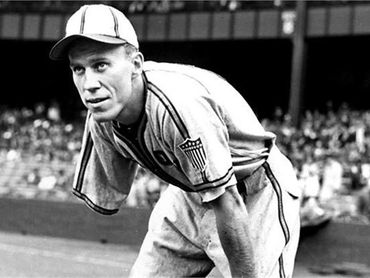

Pete Gray arrived in the majors as one of the most unlikely outfielders baseball had ever seen. Born in Pennsylvania coal country, he lost his right arm at age six in a wagon accident — a childhood tragedy that pushed him into a lifelong obsession with proving he could still play the game he loved. Gray taught himself everything: catching the ball against his body, flipping it into the air, slipping on his glove, and firing it back with astonishing quickness; hitting by whipping the bat with extraordinary torso strength; running with a kind of daring electricity. By 1945, after years in the minors and a spectacular MVP season with the Memphis Chicks, he finally reached the majors with the St. Louis Browns.

“I don’t know how much ball Pete Gray will play for the Browns,” wrote Paul Menton in the Baltimore Evening Sun, “but I doubt if he will play regularly, and certainly he wouldn’t be on the squad in normal times.” But if circumstances opened the door, Gray’s determination shoved it the rest of the way. Menton framed Gray not as a curiosity but as a study in grit — a man who spent years teaching himself the finer points of baseball until he reached the major leagues even in peacetime. “He has earned his chance to wear a major-league uniform,” Menton wrote, noting that baseball had been “the most important thing in his life,” that he spent “long hours learning how to play,” and that he made “few mistakes.” The Browns weren’t paying him “for decoration on their ball club,” Menton emphasized. Gray had earned every inch of it — even if wartime rosters helped his cause.

Then came his debut, and St. Louis reporters wasted no time planting their flag: “You have to see it to believe it. This one-armed Pete Gray is no baseball freak,” declared the St. Louis Dispatch. Gray went 1-for-4, but it easily could have been 2-for-4. In the fifth inning he “caught hold of the leather” and sent a hard drive toward right-center, only for Detroit’s Roger Cramer to make a full-speed, highlight-reel grab just as the ball was about to hit the turf. After the game, Gray summed up his duel with Hal Newhouser simply: “That lefthander was really rough… he threw me every pitch in the book.” His hit came later: a sharp smash over second in the seventh that Eddie Mayo knocked down but couldn’t turn into a play. Gray took second on a passed ball, and his aggressive base running left the Tigers jittery.

Reflecting on the afternoon, Gray said: “It wasn’t too good, but it sure was better than my first game for Memphis in the Southern Association.” And his manager, Luke Sewell, offered the verdict that mattered most: “He’s ok for my money. I like his work.” St. Louis fans, American League scribes, even the skeptical Eastern writers all agreed: the kid could play. And on a club held together by wartime patchwork, Pete Gray’s debut wasn’t a stunt — it was a moment of genuine baseball wonder.

Part III: Joe Nuxhall’s Not-So-Storybook Debut

Wartime baseball didn’t just open the door for unlikely heroes like Pete Gray — it also produced the kind of experiments that made sportswriters rub their eyes and re-read their own copy. Case in point: Joe Nuxhall, the “husky portsider” from Hamilton, Ohio, who had graduated from Wilson Junior High School the previous week and would not celebrate his sixteenth birthday until June 30. Newspapers repeated the detail with a tone that hovered somewhere between disbelief and gentle amusement: a junior high pitcher was about to face the St. Louis Cardinals.

If the moment seemed absurd, there was a logic behind it — at least the kind of logic only wartime baseball could invent. The Reds had signed Nuxhall as a curiosity in 1943 because his father came along to supervise him; he was so young that a parent had to legally be in the dugout. Cincinnati viewed him as “future material,” someone to stash until the war ended. But by mid-1944 the roster was so shredded by military service that the club quietly activated anyone who could still throw strikes. When the season opened, Nuxhall was on the active list not because he was ready, but because he happened to be under contract and, technically, available. Even then, the Reds planned to hide him — until June 10 turned into an 18–0 farce and a desperate manager scanned the dugout and landed on the teenager who had been in school nine days earlier.

Nuxhall’s stat line became the kind of debut that reporters described with a wince and a shrug. He worked two-thirds of the ninth inning, gave up five runs on five walks, two singles, and a wild pitch. The Cardinals padded the score to 18–0, and one paper — after tallying the whole mess of 21 hits, 14 walks, and various defensive errors — declared the afternoon “long and ludicrous.” It wasn’t clear whether they meant the game, the inning, or the entire wartime season. And yet, in its own way, the debut was perfectly on-brand for 1944. Gray’s story showed the heroic side of a depleted league. Nuxhall’s showed the uncomfortable edge — the moment when baseball’s improvisation bordered on farce. He wasn’t ready. Everyone knew it. But wartime baseball didn’t care. It handed him the ball anyway.

Part IV: Bert Shepard — The One-Legged Pitcher

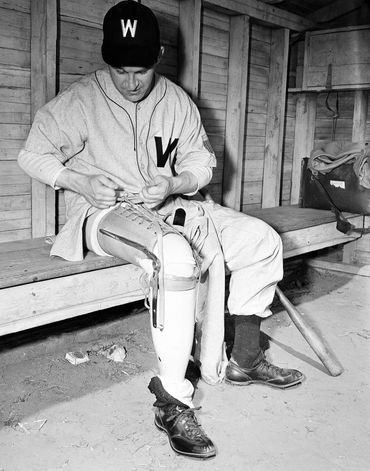

Wartime baseball had already delivered the improbable — a one-armed outfielder, a 15-year-old pitcher, rosters filled with machinists, teachers, and part-timers — but nothing quite prepared fans for the sight of Bert Shepard, the Army Air Forces fighter pilot who had lost the lower part of his right leg in aerial combat over Germany. By August 1945, he was back on a mound in Washington on an artificial leg, trying to pitch in the major leagues.

Shepard had been a curiosity all summer, appearing in a string of exhibition games after his remarkable recovery. The Associated Press declared him “A-1 in relief,” a wink at military classifications that every reader understood. His official debut finally came on August 4, 1945, in the second game of a doubleheader against the Boston Red Sox — a game the Senators were already losing badly. He relieved Joe Cleary in the fourth inning and, according to multiple papers, the crowd buzzed with anticipation before he even threw a pitch. Shepard didn’t disappoint. Using a fluid, balanced delivery honed on his prosthetic leg, he worked five and one-third innings, allowing only three hits and one earned run. The crowd gave him a standing ovation as he walked to the mound and again when he left.

It was, by any measure, a triumph — the kind of performance that would have earned more chances in any other season. But timing wasn’t on his side. The war was ending. Veterans were returning. Roster exemptions evaporated almost overnight. By late August, stories were already noting that Shepard would be awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross at the ballpark during a Senators–Yankees twilight doubleheader — a sign of how the narrative around him had already shifted from “pitching prospect” to “war hero on loan.” And so his major-league career ended almost exactly where it began: one shining, emotional afternoon on a leg he wasn’t supposed to be walking on, let alone pitching on.

Part V: After the War

Pete Gray never repeated the magic of his debut season. After 1945 he bounced around the minors, his hitting exposed once major-league pitching returned, but he remained a popular barnstorming draw for years and ultimately became a symbol of wartime baseball’s unlikely heroes. Joe Nuxhall returned to the minors after his rough 1944 cameo, grew into his frame, and worked his way back to Cincinnati — where he became a reliable left-hander across 16 big-league seasons and later the beloved longtime radio voice of the Reds. Bert Shepard never pitched in another major-league game, squeezed out by returning veterans, but he stayed in baseball as a minor-league manager and roving instructor. He later became a motivational speaker and remained a celebrated figure for his extraordinary recovery and one-game triumph.

Part VI: Alternate Diamond — Would Pete Gray Have Stuck in a 30-Team Major League?

We asked our Alternate Diamond AI a simple question: if Major League Baseball had 30 teams in 1946 instead of 16, would Pete Gray have stayed in the big leagues? When the war ended, the majors snapped back to their old reality — 16 clubs, about 400 roster spots, and returning stars like DiMaggio, Feller, and Williams. Gray could hit fastballs, outrun infielders, and make dazzling plays with one arm, but breaking balls beat him, and his swing lacked power. In a smaller league, the math wasn’t kind.

Yet Gray wasn’t just another player — he was an attraction. Stadiums filled to see him, newspapers chronicled his every move, and his debut was front-page news. In a 30-team world, that would matter. Expansion teams have always valued more than just numbers. The 1977 Toronto Blue Jays kept charismatic slugger Otto Vélez for the excitement he generated. The 1998 Tampa Bay Devil Rays signed aging Hall of Famer Wade Boggs to lend credibility and draw crowds. Teams like those pick players who sell tickets, create identity, and give fans someone to root for. Gray would have been that kind of player. His one-armed .218 average remains one of the sport’s most astonishing feats, and his speed, daring, and determination would have made him the perfect “identity guy” for an expansion club hungry for headlines.

Verdict: On the Alternate Diamond, at least one team drafts him without hesitation. Maybe two. Gray plays a few more seasons — a fourth outfielder, pinch-runner, and nightly marvel. In the real 1946, the music stopped and he had nowhere to sit. In a 30-team universe? The kid with one arm keeps playing.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

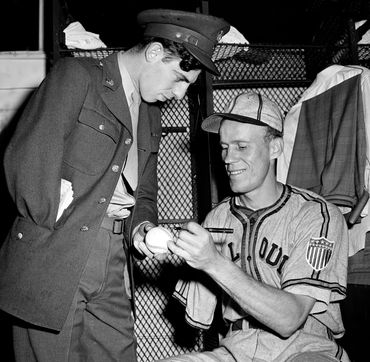

Gray and Shepard posing in 1945.

Photos of Gray, Nuxhall, and Shepard, World War II suprising major-leaguers.

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.