The Federal League

Part I: The New Boys in Town

In modern American sports, stability is almost boringly reliable. For more than half a century, the Big Four leagues — MLB, the NFL, the NBA, and the NHL — have ruled their turf with unshakable monopolies. A few upstarts have strutted onto the field — the USFL, the XFL, assorted basketball and hockey experiments — but they all fizzled before denting the majors’ dominance. Baseball’s empire has been even more durable. The last time anyone truly tried to break its grip was more than a century ago, when something called the Federal League declared itself the sport’s third major circuit. In the spring of 1914, for a few heady weeks, it looked like they might actually pull it off — a full-scale baseball rebellion, complete with parades, packed stands, and genuine belief that the game’s old order might finally fall.

That optimism didn’t come out of nowhere. By 1913, baseball’s labor peace was an illusion held together by the reserve clause — a contract quirk that bound players to their teams indefinitely and gave owners the power to set salaries by decree. Discontent simmered quietly for years, until a group of wealthy outsiders decided to weaponize it. The new Federal League promised greater freedom — arguing against the reserve clause, offering better pay, and giving many ballplayers the opportunity to choose their team. It also promised opportunity for fans in cities the majors had ignored — places like Indianapolis, Buffalo, and Baltimore, which had strong baseball traditions but no big-league teams. It was part player revolt, part civic uprising, and for a brief, noisy moment, it felt like the old baseball order might actually be in trouble.

Part II: The Outlaws Arrive

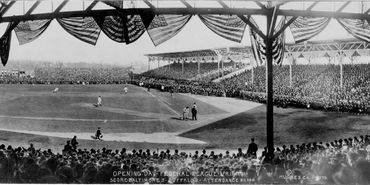

The spring of 1914 brought baseball’s grand experiment to life. After months of rumor, ridicule, and legal wrangling, the Federal League — dismissed by many as a half-baked rebellion — threw open its gates to delirious crowds across the country. It wasn’t just another minor-league debut. For a few shining weeks, the Federals seemed like the future of baseball itself.

Baltimore: The City That Went Federal

No city embraced the new circuit more than Baltimore. As one reporter quipped, the excitement stretched “from the Mayor down to the muddiest-looking street urchin.” Another paper marveled at “leather-lunged fans, perched in every conceivable part of the enclosure, with several thousand more on the outside looking in from tree and house tops and even telegraph poles.” It was, as the Sun declared, “a mighty big send-off for the Federal League.”

The city practically declared a holiday. “Everyone who is a baseball bug and others who do not pretend to be bugs were on hand,” one account read. The 25,000 who packed the new park — plus the thousands craning from rooftops — made it clear that the long-minor Baltimore had found its big-league redemption. After twelve years without top-tier ball, the Federals had filled the void left when John McGraw took his Giants north.

Adding to the drama, McGraw and his New York Giants were in town that very day, playing an exhibition against Jack Dunn’s Orioles virtually across the street from the new Federal League Park. But as one paper put it, the Giants’ game was merely “a side show affair, for all Baltimore turned out for the Federal League’s opening.” Even the mighty McGraw couldn’t compete with the city’s newfound Federal fever.

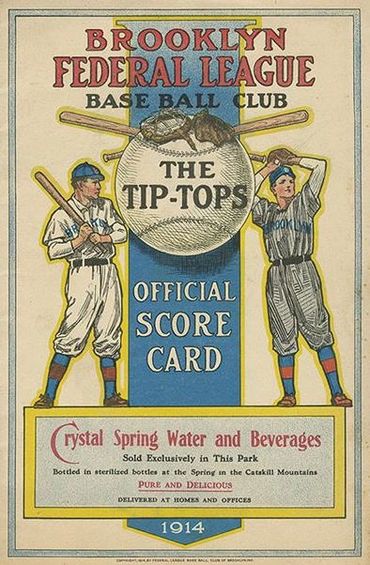

The Tip-Tops Make Their Case

In Pittsburgh, the debut of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops brought the same spirit of curiosity and civic pride. The Brooklyn Eagle called the game “extremely satisfactory,” declaring that the Tip-Tops “played a brand of ball that was up to major-league standards.” Their owner, Robert Ward, left no doubt about his satisfaction, remarking, “That’s the baseball we expect to see.”

The Tip-Tops’ performance, clean and crisp, proved that the Federal League wasn’t just an upstart novelty. The local press praised the new uniforms, the energy of the players, and the crowd’s enthusiasm. For one afternoon at Exhibition Park, the Federals showed they could match the polish and spectacle of Organized Baseball — and maybe even outshine it.

The celebration began long before the first pitch, as a parade of over a hundred automobiles and carriages — led by a brass band — wound through the downtown streets, cheered by throngs along every curb. “It seemed as if everybody in Pittsburgh was interested in the opening,” the Post-Gazette reported. The Sixth Street Bridge swelled with fans streaming toward the park, every one of them eager to see if the new league could live up to its promise.

“Crowd? Huh! Of course there was some crowd,” one reporter laughed. Expo Park, “taking on a new lease of activity,” saw more than 21,000 in attendance — a record for Pittsburgh’s North Side. Once the game began, the local club “spilled plenty of pepper,” fighting for every run and chattering nonstop from the field. “Time and again the voices of the three outfielders could be heard distinctly in the grandstand,” the paper noted. It was gritty, high-energy baseball — the kind of lively, spirited play that made even skeptics admit the Federals belonged.

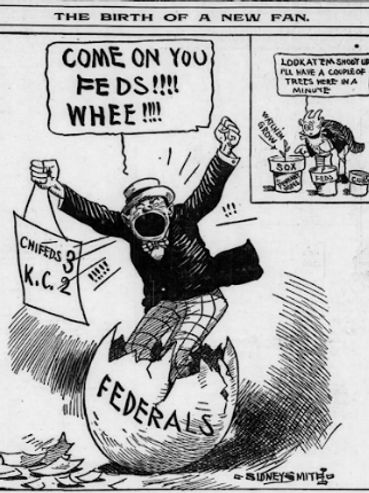

Kansas City: A Small Park, a Big Moment

In Kansas City, where big-league baseball had been gone for two decades, the enthusiasm burned just as bright. Nearly 8,000 fans — “jubilant baseball followers,” one writer called them — poured into the modest Federal League park to see George Stovall’s Packers face Joe Tinker’s Chicago Federals. Though Chicago won 3–2, the hometown crowd was ecstatic simply to see major-league caliber baseball return. The Star reported that Kansas City “took on the pride and enthusiasm of big leaguers after a lapse of twenty years.” Every seat and bleacher space was filled, and another thousand might have been packed in if the park had been larger. “Consequently,” the paper concluded, “it is taken that Kansas City is for the Federal League.”

Before the first pitch, the pregame festivities were pure civic theater. The players of both clubs marched across the field behind a brass band while a moving picture man “shot them from all angles.” League president James A. Gilmore rode in the parade alongside Mayor Jost of Kansas City, Missouri, and Mayor Green of Kansas City, Kansas, who later teamed up for a comical “battery stunt” on the diamond. Jost’s first two pitches were “reckless,” one reporter noted, but his third “split the plate.” Mayor Green dropped the catch, and Joe Tinker — “a regular Thespian, edging in as close as possible” — snagged the ball before it hit the ground, to the delight of the crowd.

Many fans had come to the park skeptically, unsure whether the Federals could truly deliver a first-rate product. But by the third inning, the doubts had vanished. “They seemed to be watchful, as if fearing a bunco game,” one account said, “but before the contest was three innings old they began cheering.” When the Packers rallied late, “the throng went into a bedlam of joy.”

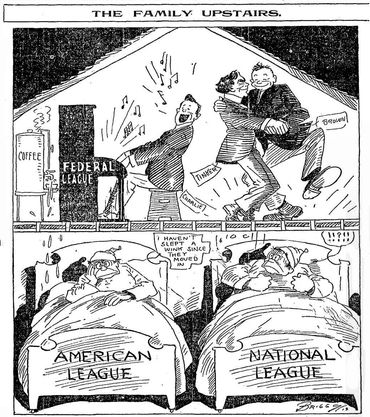

In St. Louis, the Post-Dispatch captured how swiftly Organized Baseball’s laughter had curdled into alarm. “Six months ago,” they wrote, “owners of organized baseball clubs were complacently handing the ha, ha, ha to all reports of Federal League competition.” The “pooh-pooh brigade and tut-tut boys,” had mocked the so-called outlaws. Now, they’d gladly pay “a million dollars to have conditions as they were after the close of the 1913 season.”

The Federals, the Post-Dispatch observed, were no longer a sideshow. “The outlaws have grown strong and popular. They will not only last the season out but will prepare to go on for several seasons — a menace to minor leagues and major leagues alike.” His blunt prediction: Organized Baseball could no longer ignore the “enemy outside the gates.” Sooner or later, one of three outcomes awaited — “Annihilation, Amalgamation, or Recognition.”

A War Over Players

That same week in St. Louis, the conflict turned hot. When Ban Johnson learned that George Stovall’s Kansas City Federals had signed Earl Hamilton — still under contract to the Browns — he “declared war.” Johnson vowed that “the American League will stop Hamilton if it takes every dollar in the treasury.” Federal League president James Gilmore countered by sanctioning Stovall’s raid: “Organized baseball tried to wreck Stovall’s Kansas City club and took away Blanding and Baumgardner, who had signed legal contracts with him.”

The Hamilton dispute was only one skirmish in a much larger campaign that came to be known as the Player Wars. The Federals aggressively pursued discontented stars and solid regulars alike — anyone tired of the reserve clause’s grip. Chicago enticed Three Finger Brown, still a legend on the mound; Pittsburgh landed Claude Hendrix; Baltimore signed George Stovall himself; and the Chicago Whales even tempted Joe Tinker to come aboard as player-manager. Across the majors, owners fumed as contracts were broken and lawsuits flew. Organized Baseball portrayed the upstarts as reckless pirates, while the Federals painted themselves as liberators giving players freedom and fair pay. It was open-season chaos, and for the first time in decades, the baseball establishment looked genuinely nervous.

Part III: The Hint of Forever

For a day, it all felt unstoppable. Baltimore and Pittsburgh were delirious, Kansas City was reborn, and the big leagues were on the defensive. But that sense of permanence was short-lived. The Federals soon learned that enthusiasm and ambition weren’t enough to sustain a league against baseball’s entrenched power. Travel costs soared, attendance dipped in cities already loyal to major-league teams, and player salaries ballooned beyond what the new owners could afford. Lawsuits piled up, and the majors simply outlasted them. By the end of 1915, the Federal League folded — some teams absorbed, others erased, and the rest of its dreams scattered into baseball’s folklore.

That’s a longer story for another day, but on Opening Day 1914, none of that mattered. The music was loud, the crowds were full, and for a few bright afternoons, the Federal League really did look like the future.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

At least for a while, the Feds had caught the eye of the fans.

Scenes from the Federal League, the last serious baseball competition that the Majors has had.

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.