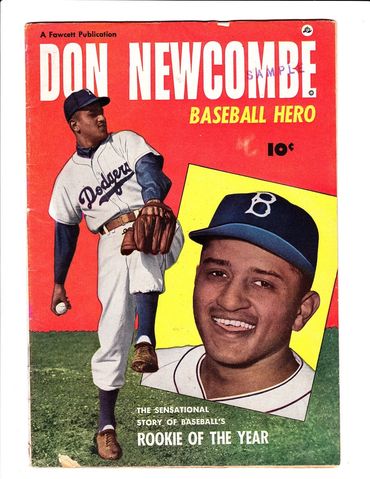

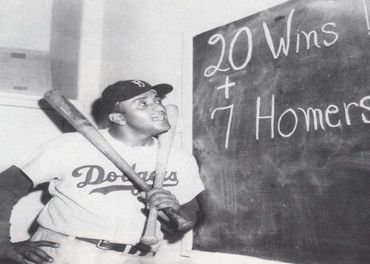

Don Newcombe: A 1950s Ohtani?

The Dodgers' Don Newcombe pitching and hitting at an elite level.

Could Don Newcombe Have Been Baseball's First Ohtani?

Part I — The Forgotten Prototype

For over a century, baseball has produced its share of phenoms, but few have bent the sport’s logic like Shohei Ohtani. A hitter who slugs like Ruth and a pitcher who dominates like Gibson, Ohtani has revived the idea that one player can do both at an elite level — an idea that, strangely, no one seriously attempted in the decades between. Even Babe Ruth, who spent 1918 toggling between the mound and the outfield (winning 13 games while hitting 29 home runs), soon gave up pitching altogether. Which raises the obvious question: was Ohtani truly one of one, or were there others who could have done it if baseball’s imagination had allowed them?

Part II — The Ponderous Pitcher

Take the case of Don Newcombe — a six-foot-four right-hander with a heavyweight build, an explosive fastball, and a swing to match. Born in New Jersey in 1926, Newcombe came up through the Negro Leagues with the Newark Eagles before Branch Rickey signed him to the Brooklyn Dodgers system in 1946, making him one of the earliest Black pitchers in the majors. By 1956 he had won both the Cy Young Award and MVP, the first player ever to claim both honors in the same season.

But for all his dominance on the mound, Newcombe was also one of the best-hitting pitchers of the 20th century. He batted .271 for his career, slugged 15 home runs, and in 1955 famously hit .359 in just 117 at-bats — a small sample size, sure, but eye-opening. Reporters couldn’t help but notice. The Associated Press called him the “ponderous pitcher whose smoking bat makes him an ace pinch hitter,” a rare double-threat in an age when pitchers were expected to bunt, not bash.

And he did it all while treating hitting as an afterthought — a diversion between starts, not a discipline. Which naturally raises the question: if Newcombe had been trained and managed like Ohtani, not restrained by the conventions of his era, just how much thunder might that swing have unleashed?

Part III — Tradition, Boundaries, and Missed Chances

It’s one of baseball’s stranger ironies: the greatest hitting pitcher of the 20th century played for one of the sport’s most innovative franchises — and no one even thought to try him as a two-way player. The Brooklyn Dodgers of the 1940s and ’50s prided themselves on breaking barriers. They were run by Branch Rickey, the same visionary who integrated baseball and rebuilt farm systems from scratch. Yet even in that forward-thinking environment, the idea of using Don Newcombe both on the mound and in the field never seems to have crossed anyone’s mind.

Part of that was simply baseball’s structure. Once a player was labeled a pitcher or a hitter, he entered a separate world — different coaches, different routines, different expectations. A pitcher who spent extra time in the batting cage might be seen as unserious about his real job. There were also the physical demands: starters then worked on three days’ rest, often logging 250–300 innings a season, leaving little recovery time for anything else.

To reinvent someone like Newcombe as a partial position player would have required reimagining pitching itself — and baseball wasn’t built for reimagination. The reserve-clause era rewarded conformity, not creativity. A player was property; a manager’s job was to win the next game, not test the limits of what one man could do. And so the game’s most progressive team — the one that broke the color line — left another kind of revolution on the table.

Part IV — The What-If Scenarios

So what would it have looked like if Don Newcombe had been given the freedom to be baseball’s first true two-way player? There are two ways to imagine it — one plausible, one pure fantasy.

In the Half-Ohtani scenario, Newcombe would have remained a starting pitcher but doubled as the first man off the bench on his non-pitching days. With no designated hitter in either league, every National League game created a pinch-hit opportunity somewhere between the sixth and ninth innings — often when a pitcher’s spot came due or a light-hitting shortstop stood in with men on base.

Newcombe could have been that weapon. In reality, he did pinch-hit occasionally — 23 times in 1955, going 8-for-21 (.381) in the role — but never on a systematic basis. What we’re imagining here is an expanded version of that: a manager who tries to get him into every game with one at-bat, treating him as a true two-way contributor. Over a season, that could easily add 80–100 plate appearances to the 80 or so he would’ve logged while pitching. With his career .271 batting average and legitimate power — and considering he hit .359 in 1955 — that’s real run production sitting unused on the bench. In a modern frame, that’s a Shohei-lite, a swing worth perhaps two or three extra wins a year.

Then comes the Full-Ohtani scenario, the one that feels like science fiction for the 1950s but still makes you wonder. Suppose the Dodgers had decided to rest Newcombe from the rotation every fifth day instead of every third, and play him in the field in between — perhaps at first base or even in a corner outfield slot. The arm strength was there, and he was a fine athlete.

In this model, Newcombe might have doubled his plate appearances again, reaching 350 or 400 in a season — enough to test what kind of hitter he could truly be. Even allowing for fatigue, regression, and the grind of cross-training, his offensive profile suggests a hitter who could have produced something like a .275 average with 20 home runs. That’s not superstardom — but it’s a middle-of-the-order bat paired with an All-Star pitcher. And that’s the part that stings a little for history: baseball’s most progressive organization of the time — the team that broke the color line, scouted the Caribbean, and invented the farm system — had in its dugout a man uniquely built to rewrite the rules again. But the idea itself simply didn’t exist yet.

Part V — The AI Alternate Diamond

This isn’t a courtroom; it’s a barstool. So we asked our Alternate Diamond Simulator to run two just-for-fun projections using Newcombe’s prime (mid-1950s) as a baseline, the 1950s run environment, no DH, and a light “fatigue tax” when he hits and pitches in the same week. Think of these as plausible ranges, not exact science.

Scenario A — “Half-Ohtani” (starter + first bat off the bench)

Usage assumptions: Normal 1950s starter workload; pinch-hit on 3–4 non-start days per week when leverage is high.

Hitting volume: ~160–180 PA (≈80 while pitching + ≈80–100 as a pinch-hitter).

Projected batting line: .275–.290 / .320–.340 / .420–.450, 8–10 HR, 28–38 RBI, 160–180 PA.

Pitching workload: 230–250 IP, 32–35 GS; ERA roughly 3.10–3.40.

Very rough WAR split: Pitching ~4.5–6.0 WAR, Hitting ~0.8–1.3 WAR → Total ~5.3–7.3 WAR.

Scenario B — “Full-Ohtani” (starter every 5th day + regular position player)

Usage assumptions: Rotation stretched to every 5th day (modern cadence), plus 3–4 starts/week in the field (likely 1B/corner OF) on non-pitch days.

Hitting volume: 420–480 PA.

Projected batting line: .270–.285 / .320–.340 / .440–.470, 18–22 HR, 68–82 RBI, 420–480 PA.

Pitching workload: 200–215 IP, 30–32 GS; ERA roughly 3.25–3.60.

Very rough WAR split: Pitching ~3.8–5.0 WAR, Hitting ~1.8–3.0 WAR → Total ~5.6–8.0 WAR.

Part VI — Full Circle: Ohtani, Newcombe, and the Limits of Imagination

The numbers, like the stories, say the same thing: Don Newcombe could have been baseball’s first modern two-way star — maybe not Ohtani’s equal, but certainly his ancestor. The talent was there, the physique was there, and even the bat speed was there. What wasn’t there was the imagination. Ohtani’s success didn’t just take superhuman skill; it took a baseball culture finally open to the idea that one player could live two lives at once. In the 1950s, the system would’ve choked that dream before it began.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

Let's feed Don Newcombe into the simulator...

Above Photos: Some photos of Don Newcombe in the 1950s, as well as his meeting with Ohtani before the old-timer's death. Instead of "20 wins + 7 homers" was there a path to 20 wins + 20 homers?

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.