Chief Noc-a-Homa and Bernie Brewer

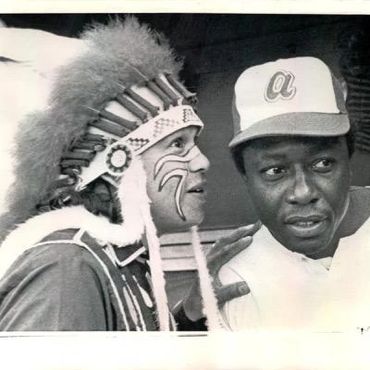

Chief Noc-A-Homa just short of mid-season form according to Skip Carey in 1985.

From Tepees to Tomahawks to Technology

Part I — Chief Noc-A-Homa: The Man in the Tepee

Baseball has always been more than a game. It’s theater, ritual, and regional identity — a mix of civic pride and personal mythmaking that plays out on a diamond. And few symbols capture that mix better than the mascots and monikers that have marched alongside the sport for more than a century. From the man in the tepee to the man on the scoreboard to a machine imagining their successors, two famed “real person” mascots show how baseball’s sideshows became part of its soul.

Before the foam suits and marketing departments, the Atlanta Braves had something stranger: a living mascot who actually worked out of a tepee in the bleachers. When the team moved from Milwaukee to Atlanta in 1966, they brought along a mechanical mascot named Big Victor — a “Redskin” automaton who was supposed to wave his tomahawk when the Braves scored but, according to local writers, “rusted away” from inactivity. None of the team’s early gimmicks had the staying power — or surreal theatricality — of Chief Noc-A-Homa (Knock a Homer, get it?).

The role’s third and longest-running performer, Levi Walker Jr., an Algonquin (Chippewa-Ottawa), took over in 1969. Born in Charlevoix, Michigan, in 1941, Walker was an insurance agent by day and, by night, a showman in buckskins and moccasins. He made his own costumes and set up an air-conditioned tepee in the left-field bleachers of Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium — a small personal clubhouse that he decorated and maintained himself.

Walker’s presence blurred the line between team mascot and independent performer. He wasn’t a corporate creation; he was a person with his own props, routines, and following. When the Braves hit home runs, he emerged from his tepee to light smoke bombs and perform what newspapers simply called a “war dance.”

Life as Noc-A-Homa could be unpredictable. Players sometimes joined the act — Cincinnati’s Pete Rose greeted him with “Hey Chief, where’s your squaw?” — while others treated him like a nuisance. Dodgers pitcher Jim Brewer made a habit of chasing him back to his tepee before games. One fan even tried to climb a rope ladder to the Chief’s tepee and nearly broke his neck. And on one infamous afternoon in 1969, a smoke bomb misfired and set the tepee on fire.

Those stories say as much about the era as they do about Walker. This was 1970s baseball — before million-dollar contracts and PR departments — when mascots mingled freely with fans, and players treated the man in the tepee as part of the traveling circus.

By the mid-1970s, Noc-A-Homa had become as much a local institution as the team itself. In 1977, Walker briefly considered leaving the role. “Like anyone else,” said the Braves publicity director, “he felt he might be happier in another job other than being a professional Indian.” But Walker returned after a short absence — an announcement which the Atlanta Constitution compared to “finding out Santa Claus had quit, but reconsidered.”

That same year, the Braves turned the act into a promotion: a giant illustration of the team’s “screaming Brave” logo was placed near Walker’s tepee, and if a home run landed in the logo’s open mouth, one lucky fan would win $5,000 — with Noc-A-Homa himself serving as the official verifier.

By the early 1980s, the act had become part of Braves folklore — and, eventually, one of its strangest superstitions. In July 1982, the team temporarily removed Walker’s tepee to add more seats. Almost immediately, the Braves went into a tailspin, losing 19 of 21 games, and fans began blaming the slump on the “Chief’s curse.” The tepee was quickly restored, the Braves went on a hot streak, and Walker returned to the field to great applause. The episode cemented Noc-A-Homa’s place in baseball mythology — equal parts charm and cringe.

That same year, Walker — by then 40 — told reporters he still prayed to “the Great Spirit” before each game and hoped to keep “leading the Braves out when I’m ninety.” He joked that Bob Horner made more money, “but spiritually, I think I do.” It was clear that by then, Levi Walker wasn’t just playing Chief Noc-A-Homa — he was him.

When the Braves quietly retired the act after the 1985 season, there was no public controversy — at least not the kind that would come later for Native mascots elsewhere. Atlanta simply moved on, replacing a living man in a tepee with a fuzzy cartoon character. The cultural reckoning hadn’t arrived yet.

Part II — Bernie Brewer: The Man on the Scoreboard

If Atlanta’s mascot once looked backward, Milwaukee’s looked up. In the summer of 1970, the brand-new Milwaukee Brewers were still fighting for attention. The team had just arrived from Seattle after the Pilots’ collapse, and County Stadium felt like a cavern of empty seats. By mid-summer, attendance was so thin that the front office’s friend Milt Mason — a 69-year-old retired Navy aviation engineer — decided to do something about it.

With the Brewers’ blessing (and perhaps a little help from the club’s operations director Marvin Milkes), Mason climbed to the top of the County Stadium scoreboard — roughly 80 feet above the field — and vowed not to come down until the Brewers drew 40,000 fans to a single home game.

Up there, he became known as “Bernie Brewer.” The team hoisted up a 24-foot Mallard trailer — fully stocked with air conditioning, color TV, a stereo cassette player, an exercise bike, a gas stove, and even a steel-grated “patio.” Local restaurants sent up dinners, reporters phoned daily, and Bernie spent his afternoons answering fan letters one by one.

During games he acted as a one-man pep rally — holding up homemade signs that read “Home Run,” “Hit,” “Steal,” or “Strike Out.” Sometimes he’d climb onto the giant clock above the bullpen and dangle his legs 100 feet in the air. “The higher I am,” he told reporters, “the better I like it.”

By August, Bernie Brewer was a regional celebrity. Kids mailed him letters, radio stations held contests, and a local pizza chain printed “Let’s Help Get Bernie Down” on employee helmets. The Brewers scheduled Bat Day for August 16 against Cleveland, handing out 15,000 Little League bats to kids 14 and under in hopes of hitting the magic number.

It worked. A crowd of 44,387 fans filled County Stadium that day — the largest since the Braves had left town — and the Brewers won 4–3. After more than a month aloft, Bernie finally descended, lowering himself by rope in front of a cheering crowd and reportedly burning his hands in the process.

Three years later, in 1973, the team honored him with a new mascot — the cartoon Bernie Brewer who slid down a beer-mug chute after each home run. Milt Mason had passed away that same year, but his stunt lived on as a tribute to one man’s audacious belief that a ball club and a city could cheer each other into greatness.

Part III — Rebranding the Braves: What AI Might Do With a Tomahawk

It’s easy to forget, in hindsight, just how common Native American team imagery once was. The Braves, Indians, and Redskins were all born in a different era — one that saw mascots like Chief Noc-A-Homa not as mockery, but as color and flair.

Time moved on, and the culture evolved with it. Cleveland became the Guardians. Washington became the Commanders. Atlanta, somehow, kept the tomahawk — and the chant that echoes through Truist Park to this day.

There’s no denying that change was overdue. Respect for Native American culture isn’t political correctness; it’s basic decency. But in the rush to rebrand, something else sometimes gets lost: history itself. The Cleveland Indians were a century of baseball memories — Bob Feller, Lou Boudreau, and Larry Doby didn’t play for the Guardians, no matter what the back of a video game card now says. When a team’s name changes, it’s not just a logo swap — it’s a rewrite of emotional history.

That’s the tension: honoring progress without erasing the past.

So we asked the AI — our in-house baseball futurist — to imagine what Atlanta might be called if the franchise ever did take that step. The goal wasn’t to be preachy or performative, but to imagine something new that still felt rooted in the region, the sport, and the fans who fill the stands.

⚾ 1. Atlanta Phoenix

The phoenix is both Southern and symbolic — rebirth from fire, like Atlanta itself rising from the ashes of the Civil War. The name captures resilience without offense, pride without appropriation.

Tagline: “From the ashes, we rise.”

⚾ 2. Atlanta Hammers

A nod to the late, great Henry “Hammerin’ Hank” Aaron — still the purest embodiment of the Braves legacy. It’s direct, powerful, and deeply local.

Tagline: “Forged in 44.”

⚾ 3. Atlanta Bravehearts

The AI’s third idea leaned toward emotion rather than geography. The Atlanta Bravehearts would honor courage itself — the spirit of competition, endurance, and resilience. The suggested logo combined a bold heart shape with a stylized “A” at its center, framed by faint winged lines to evoke motion and defiance.

Tagline: “Play with heart.”

Part IV — The Human Touch: The Atlanta Brave

That’s where the human half of this experiment stepped in. Looking over the AI’s suggestions, one word stood out — brave. What if, instead of abandoning the old name entirely, Atlanta simply redefined it?

The Atlanta Brave. Singular. Not a warrior, but a state of mind.

It would be a team name in the modern mold — like the Miami Heat or Orlando Magic — but rich in layered meaning. The word “brave” could honor multiple threads of Atlanta’s complex history: the bravery of the Civil Rights Movement, born in Atlanta under leaders like Martin Luther King Jr.; the courage of Confederate soldiers, who fought with valor even as they stood for a flawed cause; and the heritage of Native Americans, whose strength and spirit were so often caricatured yet deserve genuine respect.

In that sense, The Atlanta Brave wouldn’t erase the past — it would reconcile it. The tomahawk could be retired, the chant silenced, but the name itself could endure in a new, nobler form — one that acknowledges where it came from and who it now represents. Because maybe the best way forward isn’t to burn history down. It’s to understand it — and carry only the courage with us.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

Controversy remains in Atlanta over the "Tomahawk Chop."

Above Photos: The Atlanta Brave? It's one potential solution to the Atlanta name situation. Photos here also include the Chief and "Barry Brewer" - the real thing and mascot version.

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.