The Designated Runner

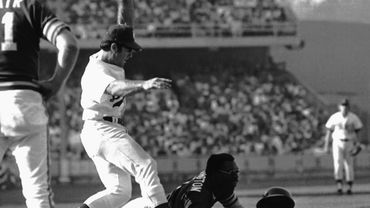

Herb Washington is picked off in the World Series against the Dodgers.

The Sprinter Joins the A's

Part I: Finley’s Latest Experiment

By the time Charlie Finley signed Herb Washington, baseball had long since learned to expect the unexpected from the Oakland A’s owner. He was the sport’s consummate tinkerer — part showman, part disruptor, and, occasionally, part visionary. In the early 1960s, Finley abandoned the team’s traditional red-white-blue look for bold Kelly green and gold — a palette so loud it practically glowed against baseball’s sea of whites and grays. He brought along a live mule mascot named Charlie-O, and he turned mustache-growing contests into civic events. The A’s became baseball’s most colorful act — literally and figuratively.

But behind the sideshow, Finley had a restless, inventive mind. He wasn’t content to win three straight World Series — he wanted to reinvent the sport while he was at it. Long before free agency reshaped the game, Finley was pushing for it, arguing that players should have the right to market their own talents. He also championed ideas that would later become staples of modern baseball — including the designated hitter and night World Series games to reach national TV audiences. Not every brainstorm caught on (his experiment with colored baseballs is now mostly a trivia question), but his imagination never lacked for ambition.

The A’s clubhouse was Finley’s laboratory, and his players were the test subjects in his ongoing baseball experiment. He meddled in contracts, meddled in lineups, and meddled in marketing — all while building a dynasty that somehow thrived amid the chaos. And in 1974, Finley decided to test his most outlandish idea yet: the designated runner.

If football had placekickers and hockey had enforcers, Finley reasoned, why couldn’t baseball have a player who did just one thing — run? In his own odd way, he was onto something. The game would eventually embrace specialization, from bullpen lefties to designated hitters to defensive replacements. In that sense, the idea of a one-skill roster spot wasn’t as far-fetched as it seemed. That’s where Herb Washington entered the picture — a world-class sprinter who had never played an inning of professional baseball. Finley signed him to a major-league contract not to hit, field, or throw, but to steal bases and score runs.

Part II: Hurricane Herb Arrives

Charlie Finley had pulled stunts before, but nothing in Oakland — or in baseball — prepared anyone for Herb Washington to be MLB’s first-ever “designated runner.” Washington had once been drafted by the Baltimore Colts as a wide receiver and had run track at Michigan State. He wasn’t a circus performer; he was a legitimate athlete. He played some high-school baseball as a first baseman, but nothing close to what the majors required.

As soon as the A’s introduced him, the clubhouse buzzed with the obvious question: Could pure speed — unpolished, unseasoned, un-baseball — really win games? Finley, predictably, thought the answer was yes and then some. Oakland writers quoted him promising Washington would “win us ten games,” a proclamation that landed somewhere between optimism and salesmanship. Maury Wills, who spent time tutoring Washington, was enthusiastic: “I’ve worked with Herb. He’s the fastest man I’ve ever seen in baseball spikes. If he learns the pitcher’s move, he’s going to cause chaos.”

Others were not impressed. Some players grumbled privately that a guy who’d never played pro ball was earning more than them. Washington’s salary — roughly $45,000 — wasn’t astronomical by modern standards, but in 1974 it was enough to draw resentment from bench players fighting for roster spots. And then there was A’s manager Alvin Dark, who delivered this comment: “I’d like to get some of those black boys who play stickball in the streets. They can hit, and they can run.”

Spring training didn’t quiet the skepticism. One late-March report bluntly called Washington “a disappointment,” noting his rawness whenever pitchers varied their looks. But the flipside — the part critics always left out — was this: sometimes the idea worked. In one early exhibition game, Washington’s presence triggered precisely the chaos Finley had envisioned. Pitchers rushed their deliveries. Infielders twitched. Outfielders rushed throws. Washington stole bases and scored runs. One columnist described it as “psychological warfare.”

Part III: The 1974 Season and the World Series Pickoff

Once the season began, Washington’s year unfolded as a series of jolts — some promising, some not so much. He appeared in 92 games, almost always as a pinch-runner, and attempted 45 steals, successfully swiping 29 of them — not a great percentage. Most came in isolation — late-inning cameos in tight games. But the flaws remained visible. Pitchers with good moves froze him. Veteran catchers baited him into short leads. And the question emerged: Can a roster spare a spot for a man who only exists in the margins of games?

Then came the moment that froze the experiment in amber. In Game 2 of the 1974 World Series, Washington was summoned to pinch-run for Joe Rudi with the A’s trailing by a run. On the broadcast, Vin Scully warned that Dodgers reliever Mike Marshall had “one of the best moves of any right-hander,” and that Washington needed to be cautious. Marshall didn’t throw over repeatedly. Instead, he stepped off the rubber three straight times, eyeing Washington, testing him. On the first actual pickoff throw, Washington was nailed — caught leaning, tagged out cleanly, a split-second too slow.

Part IV: The Pinch-Runner Paradox

Charlie Finley’s designated-runner idea usually gets written off as a carnival act. But if you strip away the circus and ask it like a front office would, the question becomes surprisingly modern: Could a pure baserunner actually be worth a roster spot?

To find out, the AI Skipper ran two tests — one in Finley’s world (1974) and one in ours (today).

In 1974, carrying Herb Washington meant Oakland opened the season without pitcher Dave Hamilton, who produced 1.2 WAR in 1973 and would again be a legitimately useful swingman in 1974. So the real 1974 baseline is: Could an elite runner generate more than 1.2 WAR on the bases? The model uses standard run-expectancy values and adjusts for reality. After all, he can't always steal. Sometimes he enters on second base, not first. Sometimes a lefty with a good move is on the mound. Sometimes the game state says don’t risk it. So AI Skipper builds an aggressive but realistic peak season for an elite baseball-savvy runner in 1974: 70 games, 40–45 steal attempts, 32–36 steals, 6–9 caught, and a few extra bases taken on contact. That adds up to roughly +4 to +5 runs, or about 0.4–0.5 WAR — good, but nowhere near Hamilton’s 1.2 WAR.

To actually surpass Hamilton, the runner would need something close to a historic baserunning season: 60 attempts in 70 games, 50+ steals, around 90% success rate, and perfect reads on balls in play. That’s essentially prime Rickey Henderson efficiency — in a player who never bats or fields.

Part V: The Modern Check

On a modern roster, the bar is lower. A typical 26th man today is a depth bat or utility defender worth around 0.0 to 0.3 WAR. So the question becomes: can a pure baserunner reliably clear 0.5 WAR and justify that roster spot?

Start with a realistic elite-runner season: about 90 games, 45 steal attempts, 35 successful steals, and 5 caught stealings — plus a few extra bases taken on contact. Using the same run-expectancy math that applied in 1974:

- Each steal adds roughly +0.18 runs → 35 steals = +6.3 runs

- Each caught stealing costs –0.32 runs → 5 caught = –1.6 runs

- A handful of extra bases on hits adds ≈ +0.5 to +1 run

That totals about +5 runs above average, and with 10 runs ≈ 1 win (1 WAR), it comes out to roughly 0.5 WAR — a legitimate edge for a bench player on a contender.

In other words, the modern designated runner wouldn’t revolutionize a team, but he’d clearly outproduce many of the glove-first or bat-light depth players who currently fill that 26th spot. For clubs chasing every marginal win, 0.5 WAR from a specialist runner isn’t a gimmick — it’s a small but real weapon.

Part VI: AI Skipper Verdict

1974: A designated runner would’ve needed a nearly historic baserunning season to beat Dave Hamilton’s 1.2 WAR. Herb Washington was never realistically going to get there.

Today: A designated runner could make sense as a modern 26th man — but only if he’s a real baseball player with elite baserunning intelligence, not a track star learning on the job. Finley wasn’t wrong about the concept. He was just forty years early — and he cut the wrong guy to prove it.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

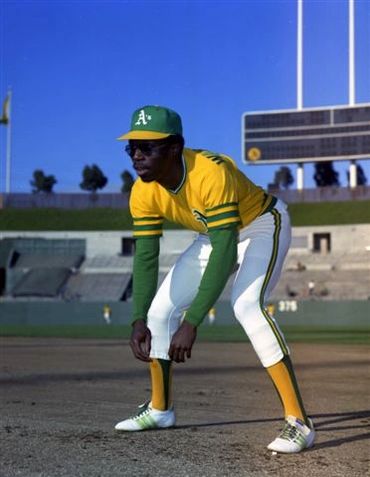

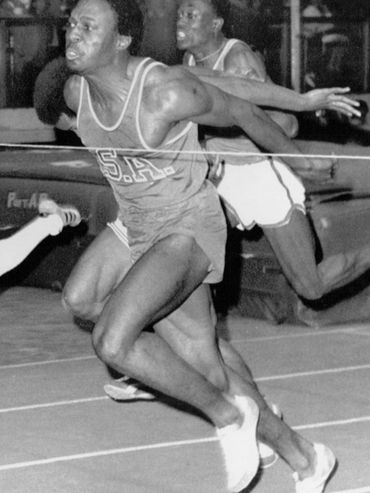

Herb Washington, Designated Runner.

Herb Washington on the field and the track. We also see Charlie O posing with manager Alvin Dark.

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.