AI Swapulator: Brock for Broglio

Lou Brock Gets Hit Number 3000

Part I — A "Stupid" Trade

On June 15, 1964, the baseball world lit up with reactions to a seemingly straightforward trade — Lou Brock for Ernie Broglio — and almost all of them agreed on one thing: the Cubs had pulled off a steal.

“It’s a great trade for the Cubs,” said Reds star Frank Robinson. “Even with a sore arm, Ernie Broglio’s better than the two pitchers the Cards got for him. As for Brock… well, he’s a pesky hitter who occasionally connects for a home run, but he’s not going to do too much.”

White Sox veteran Billy Pierce chimed in: “If Broglio’s arm is in shape, it appears the Cubs got the better of the deal.” Teammate Bob Shaw called it “a terrible trade for the Cards,” and Duke Snider said St. Louis was “gambling on Brock.” Cincinnati manager Fred Hutchinson wasn’t surprised: “The Cards were crying for outfield help.”

Within days, sports pages were filled with versions of the same sentiment — disbelief that the Cardinals would trade a proven 21-game winner for a streaky young outfielder. Robinson called it “stupid.” The near-universal consensus was that St. Louis had blundered. And yet, that “stupid” trade would become one of the most lopsided in baseball history — in the other direction.

Part II — The Deal

So how did a deal that seemed like a masterstroke for Chicago turn into a punch line for St. Louis? To answer that, we have to return to that summer afternoon when the Cubs and Cardinals swapped fortunes — and baseball philosophies — in a single phone call.

To review, on June 15, 1964, the Chicago Cubs and St. Louis Cardinals pulled the trigger on a six-player trade. Chicago, chasing pitching depth, sent 24-year-old Lou Brock and pitchers Jack Spring and Paul Toth to St. Louis for right-hander Ernie Broglio, plus Bobby Shantz and Doug Clemens. The Cubs needed arms; the Cardinals needed offense. But within weeks, it became clear that this wasn’t a normal mid-season adjustment. It was the line of demarcation between two baseball eras.

Part III — The Changing Game

In 1964, baseball was shifting under everyone’s feet. The booming homer-happy 1950s were giving way to a leaner, faster, pitching-heavy style. The strike zone had been enlarged, new ballparks favored defense, and expansion had diluted talent. Speed was suddenly fashionable again — but not yet fully understood.

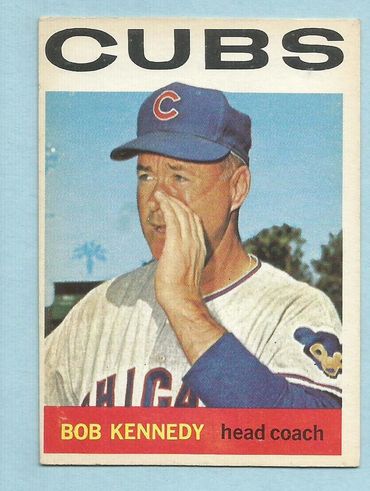

Brock, a 24-year-old with world-class acceleration, embodied that change. Yet his .257 average and rare homers in Chicago made him look expendable to a front office still thinking in power-era terms. Cubs manager Bob Kennedy, according to the Chicago Tribune, had grown “irritated by Brock’s erratic outfield play and occasionally by his unsound base running.” Another Tribune account said Brock “had fallen into some disfavor with Kennedy, a stickler for sound application of baseball’s fundamentals.” The Cubs didn’t see a prototype for the future; they saw a player who broke their rules.

The Cardinals, by contrast, were already imagining baseball on the move. Under Branch Rickey’s influence, they’d long valued athleticism and adaptability. In St. Louis, with manager Johnny Keane and teammates who encouraged aggression on the bases, Brock found oxygen for the first time. He hit .348 over the rest of 1964, stole 33 bases in half a season, and helped carry the Cardinals to a World Series title.

Part IV — The Decline of an Ace

On the other side, Ernie Broglio’s arm was already failing. The Cubs didn’t know — or didn’t want to know — that their new “ace” was pitching through severe elbow and shoulder pain. He’d logged heavy innings in St. Louis: three straight years of 200-plus innings and a 21-win season in 1960. To most outside observers, he was still a star. But internally, the Cardinals had seen warning signs — diminishing velocity, a tired curveball, and cortisone shots to keep him active.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch even noted that the trade market for Broglio had been “lukewarm,” a surprising description for a pitcher with such strong recent numbers — and one that, in hindsight, reads like a quiet acknowledgment that rival clubs suspected something was wrong with his arm.

As soon as he reached Chicago, the bottom fell out. Broglio went 4-7 with a 4.04 ERA in 1964, 1-6 in 1965, and 0-4 in 1966 before retiring. What looked like a blockbuster acquisition turned into one of the most infamous miscalculations in modern baseball. Had Broglio’s arm held up and produced even four or five more seasons like the three that preceded the trade, the deal might not have been even, but it would have been far closer. Ironically, Robinson’s “sore arm” remark showed the warning was already circulating through the league. Everyone had heard it; only the Cubs ignored it.

Part V — The Context of Race and Vision

There’s an unavoidable subtext to this deal: race. Brock was Black; Broglio was white. And in 1964, baseball’s decision-makers were still overwhelmingly white men whose frame of reference for a great player leaned toward power and polish, not speed and daring.

Players like Maury Wills, who had stolen 104 bases for the Dodgers in 1962, were rare exceptions — and often treated as curiosities rather than trendsetters. Within the Cubs’ front office, there was little imagination for how a fast, aggressive, Black player could become a franchise cornerstone. The Cardinals, on the other hand, had a long history of integrating and empowering players of color. For them, Brock wasn’t an oddity — he was the prototype of what baseball was becoming.

Part VI — Inside the Clubs

Within each front office, the logic was starkly different. Cubs vice president John Holland told reporters the team “needed pitching badly,” especially with “a string of doubleheaders we have to play later in the season.” Manager Bob Kennedy said Broglio would “step right into the rotation.” The move was framed as a way to survive the 1964 grind — not reshape the franchise.

Holland cited the readiness of minor-league outfielder Billy Ott and rookie Billy Cowan as reasons they could spare Brock. The language was that of a team trading redundancy, not potential.

The Cardinals, meanwhile, knew exactly what they wanted. Manager Johnny Keane declared, “Brock was the key to the trade, and we are very well pleased.”

Even on the personal level, the deal blindsided those involved. In one syndicated report, columnist Ed Lovitt phoned Broglio’s wife, who was stunned to learn the news. She’d thought her husband had a “permanent job” with St. Louis — proof that the trade caught nearly everyone off guard, including the Broglio household.

Outside St. Louis, the reaction was mostly disbelief. One sports editorial from Kentucky summed up the general sentiment: “It’s a cinch the Cards have traded off a good starting pitcher in Ernie Broglio, but we’re not so sure they landed any prize outfielder in Lou Brock — an anemic .251 hitter with no particular flair for the home run. But Brock may surprise.” It was about as much optimism as anyone could muster for the 24-year-old outfielder that June.

Part VII — Running the AI Swapulator

To settle this one once and for all, we fired up the AI Swapulator — our retro trade-grading machine that re-analyzes historic deals using modern metrics. The formula weighs WAR (70%), championship impact (10%), financial value (10%), and intangibles (10%) to see how each side really fared over time. When we ran the numbers on the 1964 Lou Brock-for-Ernie Broglio trade, the results weren’t just one-sided — they were historic.

The AI Swapulator Results (1964–1974)

WAR Differential – Advantage: Brock side (+57 WAR)

Lou Brock produced roughly 60 WAR for St. Louis, while Jack Spring and Paul Toth added virtually nothing. On the Cubs’ side, Broglio finished with a negative WAR, while Bobby Shantz and Doug Clemens added about one. Net: St. Louis +60.

Championship Impact – Advantage: Brock

Brock’s arrival directly fueled the Cardinals’ 1964 pennant and World Series title — and he remained a cornerstone of their 1967 championship and 1968 pennant-winning clubs. Chicago’s return produced no postseason value.

Financial Value – Advantage: Brock

The Cardinals acquired a Hall-of-Fame player at a league-average salary. The Cubs paid for an injured ace and two journeymen.

Intangibles – Advantage: Brock

Brock reshaped the Cardinals’ identity — injecting speed, style, and a new brand of excitement.

Final Score: Brock 94, Broglio 6.

This remains one of baseball’s most lopsided trades.

Part VIII — The Broader Legacy

The Brock–Broglio trade didn’t just ruin a front office’s reputation; it exposed a cultural blind spot. Chicago clung to traditional metrics, valuing strikeouts over stolen bases and reputations over raw athleticism. St. Louis, intentionally or not, embraced the game’s next evolution — speed, contact, and opportunism.

Brock went on to steal 938 bases, top 3,000 hits, and become one of the most beloved Cardinals in history. The Cubs wandered through another decade of frustration before their next sustained run of success.

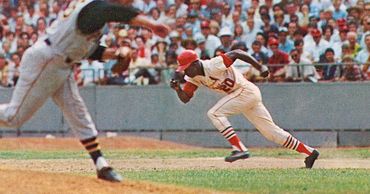

It wasn’t just a bad trade. It was baseball’s evolutionary fault line — where the old game and the new one collided, and the future ran away on Lou Brock’s cleats.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

The Swapulator is bully on Brock.

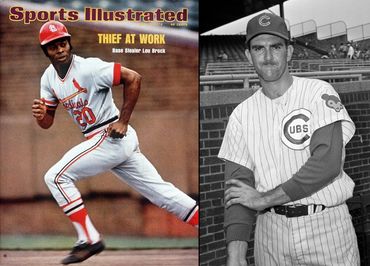

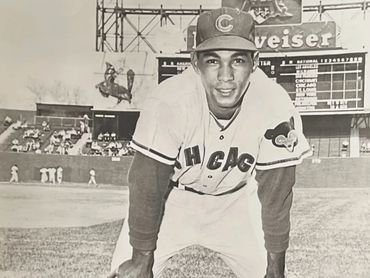

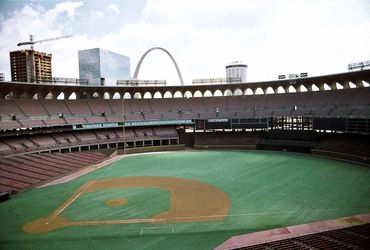

Photos of Lou Brock and Ernie Broglio as well as Bob Kennedy who liked the trade at first and Busch Stadium, which after adopting turf in 1970 appealed to Brock's game.

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.