Baseball's Forgotten Mascots

Part I — Superstition and Spectacle

Before baseball’s mascots wore feathers or foam suits, they were human — or at least treated as such.

In the early 1900s, teams didn’t trot out cartoon birds; they carried people and animals who were believed to bring luck. Newspapers covered them the way sideshow posters advertised “curiosities,” turning the vulnerable into novelties. It was the Barnum era of sports, when difference was marketed as charm and pity passed for affection.

Players rubbed hunchbacks for luck. Stray kids were “adopted” by teams. Orphans, street performers, even bulldogs were enlisted as talismans. The word mascot meant something uncomfortably close to possession.

Perhaps no story captures that uneasy mix of superstition and exploitation more vividly than the Detroit Tigers’ 1908 experiment with a so-called “lucky charm” named Li’l Rastus — a real child turned into a living prop.

Part II — Li’l Rastus, the Detroit Tigers’ “Mascot” (1908)

In the summer of 1908, the defending champion Detroit Tigers arrived in Chicago with an unlikely new addition: a young Black boy the papers called Li’l Rastus. The Detroit News described him as a “good-luck mascot” under the “care” of two Tigers players — language that feels rather chilling today, suggesting he was plucked straight from the Chicago streets and absorbed into the team with no paperwork, no guardianship, just superstition and paternalism.

One Detroit Free Press feature from July 15 ran a strange composite photo of Ty Cobb sliding home, with a tiny cut-out of Rastus literally pasted into the background . The caption called him “the champs’ new mascot,” while a smaller line — using a racial slur now omitted here — mocked his excitement. The intent was comic; the effect is haunting.

Rastus quickly became part of the team’s traveling sideshow, cheering from the dugout and appearing in wire stories as if he were a character in a serialized folk tale. But the tone soon shifted. By September, the Chicago Tribune reported on his “humiliation” in the kind of faux-sentimental language that passed for sports humor at the time:

“Rastus, with tear-dimmed eyes, watches his substitute in victory over Cub.”

According to the article, the Tigers’ “colored mascot” had been replaced by a “flaxen-haired youngster from Detroit” nicknamed Whitey, whose “careful work” might earn him a permanent bat-boy job. Meanwhile, Rastus “sat far out in center field with tear-dimmed eyes watching the Tigers pound out a victory without his assistance.”

It’s a painful little story — a literal child’s public demotion presented as comic relief. But it also closes the strange arc of Li’l Rastus’s brief baseball life: from being paraded as a good-luck charm to being quietly replaced once his novelty wore off.

Part III — The Mascot Boom (1910s)

By the next decade, the “mascot” had become a recognized baseball role — half servant, half superstition.

A syndicated story from Arizona noted that “several of the major league clubs have mascots who earn their living from the tips handed out by the players and managers,” while only one — Connie Mack’s Athletics — had a mascot “on its regular salary roll.” Teams now expected to have one, whether a bat boy, a “colored chap,” or a local curiosity who brought “luck.”

The piece read like a carnival roll call: the Giants’ quick-handed Jimmy Hennessey, the Cubs’ loyal Red Galligan, and a San Antonio mascot who opened each game with his own mock-minstrel introduction. It showed how quickly superstition had turned into theater — mascots becoming entertainment as much as omens.

Part IV — Louis Van Zelst and the Athletics’ “Hunchback Mascot” (1910–1914)

If Li’l Rastus symbolized the superstition and racial hierarchy of early baseball, Louis Van Zelst represented its turn toward sentimentality — a shift from exploitation to talisman.

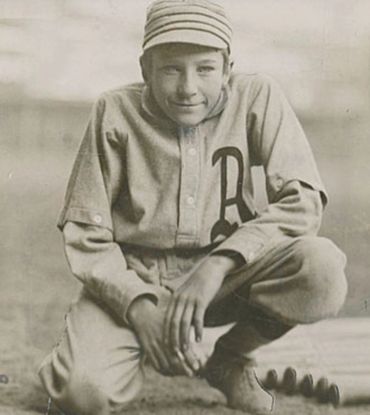

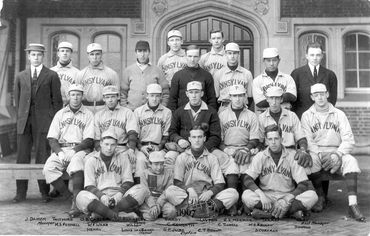

Van Zelst was a small, hunchbacked Philadelphian who became a fixture in the Philadelphia Athletics clubhouse during Connie Mack’s championship years. Born in 1895, he suffered a childhood fall that twisted his spine and left him permanently stooped — a detail that, in the cruel logic of early-20th-century superstition, only heightened his aura as a bringer of luck. Around 1910, Mack officially made him the team’s mascot, paying him a regular wage to “take care of the world’s champions’ bats and bring them luck,” as one wire story put it. Another clipping proudly announced that Van Zelst “has signed up for next season,” proof that superstition could indeed be formalized into a job description.

Players rubbed his hump for good fortune — a clubhouse ritual that mixed affection and folklore. “Mack sent him out at Cleveland to change the Athletics’ luck,” one story joked, “but Louie couldn’t stave off two of the worst beatings the Athletics got last season.”

And yet Van Zelst was clearly more than a mascot in name. He traveled with the club, received a regular contract, and even shared in the team’s postseason bounty. After one World Series triumph, a Philadelphia report described how each Athletic had a small deduction taken from his check to reward both trainer Chadwick and young Louis Van Zelst. “The Athletics rewarded their conquering mascot,” the story said, noting that new checks were cut to make sure Louie shared in the winnings. Another article added a tender detail: “Every nickel I get goes to my mother and father,” said Louis — an echo of his humility that touched reporters as much as players.

His fame even spilled beyond the diamond. One advertisement from a Philadelphia sporting-goods store proudly announced that “Louis Van Zelst, mascot of the Athletics, World’s Champions, is here — with him the only bat used by Frank Baker during the World’s Series.” Fans were invited to come see both the bat and the boy who supposedly brought it luck — a telling snapshot of how mascots were becoming public curiosities in their own right.

Other papers ran his photo under captions like “Louis Van Zelst, Hunchback Mascot Who Brings Luck to Athletics,” presenting him with the same reverent affection players felt. One clipping even noted that “the players of the team handed Louie a handsome purse last fall after they won the pennant and want him along this coming season.” He was even invited to second baseman Eddie Collins’s wedding — proof that his bond with the players extended beyond the field.

Van Zelst endured through the A’s golden run of three pennants and two World Series titles, only fading from the record after the 1914 “Miracle Braves” sweep seemed to break the spell. He died the following year, in 1915, of Bright’s Disease at just twenty years old.

Unlike Li’l Rastus, Van Zelst wasn’t discarded in humiliation — he was a gentler relic of the same era’s belief that luck could be personified. He bridged baseball’s early folklore and the modern mascot age: still human, still superstitious, but a half-step closer to the symbolic characters that would one day replace him.

Part V — The Many Faces of Luck

By the 1910s, the dugout had become a parade of curiosities.

Mascots came in every form imaginable — each one a reflection of what early baseball found amusing, pitiable, or “lucky.”

There was Barney “Rocks” Pierce, the 42-year-old, 42-pound man hailed as “Buffalo’s old baseball mascot,” drawing crowds simply by sitting outside a bank. There was the Houston Buffs’ abandoned baby, passed from player to player like a team pet; and Slugger, Yale’s bulldog, shot by police after mauling a child while the Washington Herald mourned the dog’s “tragic end” as bad luck for the team.

In San Francisco, fans adored “Doc,” the Seals’ middle-aged backstop mascot, who caught foul balls for a dollar a day while showing off a wardrobe of “rainbow-colored uniforms” provided by management. And in one unforgettable International News Service photo, the Athletics’ enormous Emery Titus was posed beside the Yankees’ tiny boy mascot Babe Shields, the caption dubbing them “the heavyweight and the bantamweight.”

From children to dwarfs, hunchbacks to “fat men,” dogs to infants, every form of difference could be rebranded as charm — everybody, a potential omen.

Part VI — Epilogue: From Flesh to Foam

By the mid-20th century, superstition softened into entertainment. The “living mascots” of the Deadball Era — Rastus, Van Zelst, Rocks, and countless unnamed others — gave way to cartoon creations like the San Diego Chicken and the Phillie Phanatic. The laughter stayed, but the stakes vanished.

Baseball no longer carries children from the streets or rubs a man’s back for luck. Instead, it sells plush replicas of creatures who dance on dugouts — still mascots, but mercifully, no longer human.

Part VII — Imagining a Kinder Mascot

After a century of strange and often sad stories, we wanted to end on a lighter note.

In the Deadball Era, teams treated people — and sometimes animals — as living charms. But there’s no reason they couldn’t have created something whimsical instead. Synthetic fabrics didn’t exist, but imagination did. So we asked an AI to dream up what a proper 1910-style baseball mascot might have looked like.

For this experiment, we chose the Philadelphia Athletics, the team most deeply entwined with baseball’s early mascot myths. Today the A’s have Stomper the elephant, a legacy of Connie Mack’s old “white elephant” emblem. But imagine if, in 1910, Mack had introduced a costumed elephant to the field instead of Louis Van Zelst — a plush, turn-of-the-century pachyderm with bowler hat and suspenders, dancing across Shibe Park between innings.

That’s the kind of mascot baseball could have had all along — one that made fans smile without making anyone the punch line.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

We asked our AI to create a 1900's era mascot for the Athletics. Meet our A's Elephant!

Mascots old and new including Van Zelst and Li'l Rastus.

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.