The Spite Fence

No footage that we could find exists of a home run clearing Shibe Park’s 31-foot “spite fence," but an AI recreation using MLB The Show gives a sense of how a blast might have looked sailing into 20th Street.

The Spite Fence at Shibe Park

Part I — Hardball in Hard Times

By the winter of 1934, the golden glow of baseball’s Roaring Twenties had gone gray. The Great Depression had cut major-league attendance nearly in half from its pre-crash peak. Owners who once counted gate receipts by the tens of thousands were now counting pennies. Even the proudest dynasties were pawning off their stars.

No franchise felt that fall harder than the Philadelphia Athletics. Only a few years earlier they’d ruled baseball — five pennants in a decade, three World Series titles, a roster so rich with talent that Connie Mack had to break it apart just to balance the books. Now the grandstands at Shibe Park were bare. The club had sold Foxx, Cochrane, Grove, and nearly every draw who’d once filled North Philadelphia’s summer nights. The empty seats spoke louder than the band ever had.

Across 20th Street, though, business still thrived — sort of. The rowhouses there had perfect sightlines into right field. For twenty-five years, neighbors had watched games from rooftops and top-floor windows, even building wooden bleachers and charging a quarter a seat. During the 1929 World Series nearly 3,000 people watched from those makeshift stands. It was a little side hustle that felt harmless while the A’s were winning and everyone was making money. But by 1934, with the ballpark and the neighborhood both struggling, that friendly understanding started to feel like a leak in the dam.

Part II — The Iron Grudge

In December 1934, the Shibe family decided enough was enough. Jack Shibe, who had inherited control of the club, ordered a corrugated sheet-iron wall built atop the low right-field boundary along 20th Street — an extra twenty-odd feet of steel meant to blot out the freeloaders’ view. The new barrier stretched from the foul line toward the flagpole in deep right-center, towering nearly thirty-one feet high and reaching some 450 feet from home plate. The metal’s rippled surface gave balls unpredictable ricochets — sharp clanks, dead bounces, and the occasional carom that sent outfielders scrambling like pinball flippers.

The Philadelphia Inquirer broke the story with a wry smile: the rooftop crowd “received the news with mouths way down at the corners.” A later op-ed in another paper laid out the whole story — the way 20th Street homeowners had first built bleachers during the 1931 World Series, discovered a new source of income, and never took them down. By 1934, those rooftop seats were stealing paying customers from the turnstiles. So Shibe and Mack, the piece explained, finally “got together and decided to elevate the outfield fence.”

When word of the plan spread, one rooftop regular summed up the mood with a shrug that could have come straight out of the Depression itself: “Well, the team is all shot up anyway, so what’s the difference? Since Connie Mack sold Al Simmons and Lefty Grove, the team’s no good anymore.”

When the season began, the barrier quickly lived up to its nickname. The Washington Star reported that the “spite fence” had already cost the Nationals two home runs, and one Philadelphia writer claimed that twenty balls hit by American League sluggers had slammed into the wall and bounced back into play — loud outs that would have been homers in any other park. “I couldn’t hit a golf ball as far as that one,” Washington’s Joe Kuhel said after one such drive.

But justice, as one writer put it, “had prevailed.” The A’s lost as many home runs to the fence as they saved. Even their own stars — Jimmie Foxx and Bob Johnson — watched long drives clank off the new iron wall. And when the accounting was done, the score stood about even. One wry columnist summed it up perfectly: “People who live in glass houses should not throw stones. Baseball clubs depending upon home runs to win games should not build high fences around their own parks.”

It was a Depression-era standoff: homeowners who’d once built their bleachers out of optimism now saw them eclipsed by steel and resentment; team owners who’d once courted community goodwill were fighting for every dime. The Shibes hadn’t just raised a wall — they’d drawn a line between two kinds of poverty, the kind you endure on a city street and the kind you measure at the ticket window.

Part III — Postscript: The View from 1939

Four years later, the neighbors were still at it — only this time, they were complaining about too much visibility. When the A’s and Phillies announced plans to host night games at Shibe Park in 1939, twenty-five nearby residents marched to a zoning hearing to protest the idea. They warned that the new floodlights would turn their bedrooms into “baby disturbers,” “health hazards,” and “all-around nuisances.”

Then came the punch line. A board member asked how many of the protestors had once rented out their rooftops to paying spectators before the right-field fence went up. About a dozen sheepishly raised their hands.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

20th Street in 1910 and today.

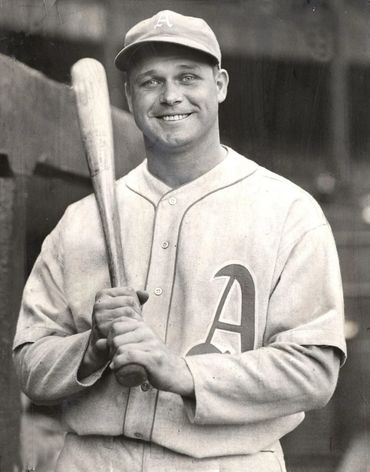

Above: Various views of Shibe Park including fans perched above 20th Street during the 1910 World Series as well as Connie Mack and slugger Jimmy Foxx.

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.