When Baseball Went to Drill

Part I — A Strange Sight on a Baseball Field

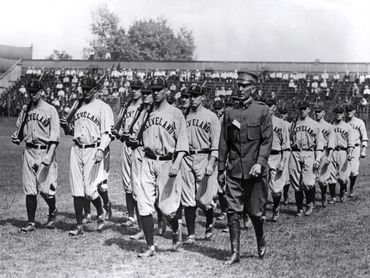

To modern eyes, the old photos look almost like parody. Ballplayers in baggy flannel uniforms march stiff-legged across the infield, often bats perched on their shoulders like rifles, coaches barking cadence while the crowd cheers. It feels half musical, half mock-military — as if the nation’s pastime were auditioning for the Army. You can almost imagine a real soldier walking out of the dugout to slap some sense into them.

And yet, no one at the time seemed to think it was absurd. In the spring of 1917, as the United States entered World War I, every corner of American life was expected to prove its patriotism. Ban Johnson’s American League — filled with young men of draft age — faced an uncomfortable question: what business did grown men have playing a little boy’s game while other young men were heading off to war?

The “drills” were their answer. Under Johnson’s orders, teams lined up in formation before games, marched across the diamond with bats for rifles, and saluted the flag while Army officers looked on. The press called it “preparedness.” To some, it was genuine moral training — a way to ready men for service. To others, it looked more like public relations: baseball covering its own hide, showing just enough militarism to convince the country it deserved to keep playing.

So what was really going on? Were these players honestly trying to prepare for combat? Were they staging a patriotic performance to keep the turnstiles spinning during wartime? Or was it something in between — a ritual vague enough to satisfy both the believers and the skeptics?

Whatever the answer, the images still unsettle. The players look dutiful, the crowd approving, the mood oddly earnest — a moment when America’s national game blurred the line between sport and soldiering.

Part II — Ban Johnson’s Army

If baseball was going to march into wartime respectability, it would do so under Ban Johnson’s command. The American League president, never shy about turning a moral crusade into a publicity campaign, ordered every club in 1917 to begin “close-order drills” before games. Players were to line up in neat rows, march in step, salute the flag, and generally look like they could take Paris by storm — if Paris happened to be ninety feet away.

To sweeten the deal, Johnson offered a $500 prize for the best-drilled team in the league — which sounds noble until you realize it was the baseball equivalent of giving out a blue ribbon for Most Patriotic Shuffle. Soon newspapers were breathlessly tracking each club’s progress.

In Washington, the local nine embraced their new regimen with gusto. The Washington Times declared the Senators “took to it like ducks to water,” while a visiting colonel beamed that they were “the best raw material I have ever seen.” Whether the colonel truly believed this or simply enjoyed being quoted is hard to say, but the paper did its part — blending baseball coverage with a dash of military fantasy.

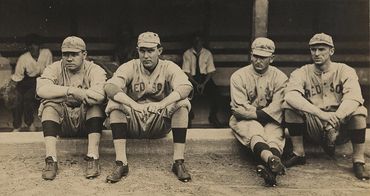

Not everyone marched so briskly. The Red Sox dragged their cleats, prompting at least one New York headline to label them “slackers.” In 1917, that wasn’t just an insult — it was fighting words. Once that label appeared in print, you could practically hear Ban Johnson’s mustache bristle from Chicago.

Other cities were less reverent. A St. Louis paper offered the sharpest jab, writing: “Keep your mind on this - All that the baseball players learned about military affairs during their spring training wouldn't enable an army of them to cross the street, if ordered to.” It was classic Midwestern skepticism — a reminder that not everyone was convinced baseball’s sudden patriotism amounted to much more than synchronized bat-waving.

Several papers even felt compelled to reassure readers that the drills were not being treated as a joke. League officials admitted they had worried players might burlesque the exercises or turn them into slapstick, but reporters hastened to insist — sometimes a little too eagerly — that no such thing occurred. The athletes, readers were told, went about their marching with seriousness and discipline, taking their orders as solemnly as if the crowd were not watching. The very need for such assurances, however, hints at how easily the spectacle might have tipped into parody.

The drills also acquired a second justification: visibility. One Minneapolis paper argued that the sight of fifty or sixty well-trained athletes moving in formation before a game could help recruit volunteers — a kind of patriotic advertisement staged between batting practice and first pitch. Another wire story claimed the regimen had transformed players from “slouching to the plate” into men who carried themselves erect, brisk, and obedient, whether in uniform or civilian clothes. Baseball, it seemed, was discovering that military posture photographed well.

By Opening Day, the experiment reached its fullest expression. In New York, troops were reviewed, bands played, and players marched in formation before the crowd. Some reportedly expressed disappointment that they would not be issued regulation rifles for the display, settling instead for their bats — which, for novelty’s sake, were occasionally handled like firearms during mock maneuvers.

Behind the ceremony, however, the practical payoff became clear. Johnson publicly claimed that league officials had received assurances from military authorities that properly drilled players would be left alone until the season ended. Whether the drills truly constituted preparation or merely paperwork dressed up as patriotism is debatable — but the result was not. The American League played on through 1917, gates stayed open, receipts kept flowing, and most players were not drafted until autumn.

Ban Johnson had his army.

And, for the moment, he kept his league.

Part III — The Truth about the Drills

So what, in the end, were these strange, bat-wielding drills actually about? In 1917, they were presented three ways at once. To some military men — and to Ban Johnson himself, at least in public — the marching was treated as legitimate preparation, proof that ballplayers were being shaped into soldiers-in-waiting. To fans in the stands and readers at home, it was unmistakably a performance: patriotic pageantry meant to show that baseball was “doing its part,” perhaps even inspiring enlistment through spectacle.

But hovering beneath both explanations was a quieter, more practical motive — one no parade ever admitted. The drills offered baseball a shield. They gave league officials something to point to when critics asked why draft-age men were still playing a game. And sure enough, the strategy worked. Players stayed on the field, the season went on, and the box office stayed open.

The marching may have looked like military readiness and sounded like national service, but its most reliable result was economic. Baseball wasn’t training for war so much as training an argument — one that let it keep playing while the country fought.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

Our AI whipped up this cartoon on the subject of players drilling during World War I.

Soldiers marching, sometimes with baseball bats, sometimes with rifles in 1917 and 1918. Ban Johnson pushed the plan while the Red Sox were seen as "slackers by some. Gen. Leonard Wood, commander of the Eastern Department, reviewed the baseball "troops."

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.