“AI Truth-O-Meter: The "Hitless Wonders"

Part I — Were the 1906 White Sox Really the “Hitless Wonders”?

The 1906 Chicago White Sox won a World Series while carrying a nickname that implied they had no business winning anything at all. But was it true? Were the 1906 White Sox really a team that won a title without an offense?

On the surface, the case seems airtight. By the standards of the day, the White Sox were unimpressive at the plate. They finished 15th out of 16 major-league teams in hits, dead last in the American League, and managed just seven home runs all season — a total that would look anemic even by dead-ball standards. Batting average, the era’s most cherished statistic, did them no favors either, reinforcing the sense that this was a team surviving on something other than bats.

And yet, here’s where the story gets interesting. For all their supposed hitlessness, the White Sox finished sixth out of fourteen teams in runs scored, above league average. They didn’t bash teams into submission; they wore them down. They led the American League in walks, struck out less than any AL club, and turned contact into movement. Productive outs mattered in 1906, and the Sox made plenty of them. Against right-handed pitching, they went a remarkable 71–39, quietly exploiting the matchups that mattered most.

In other words, they didn’t hit often — but they hit enough, and they scored more than teams that looked far better on paper. They turned patience and contact into steady movement around the bases. Add elite pitching and airtight defense, and you get a team that wins without ever looking the part. Their nickname would be put on trial in full view of Chicago in the 1906 World Series.

Part II — October, and the Sound of Bats

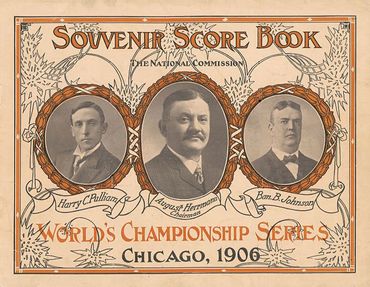

On paper, the script had already been written. The 1906 Chicago Cubs arrived at the World Series as one of the most dominant teams the game had ever seen, winners of an astonishing 116 games and owners of a roster that looked superior in nearly every conventional way. They hit more, they scored more, they pitched just as well, and they carried the confidence of a club that had spent six months bludgeoning the National League into submission. Across town, the White Sox arrived dragging a nickname that made them sound like a statistical accident. The Series itself — baseball’s first all-Chicago championship — was framed as a referendum not just on two teams, but on two philosophies. But when the White Sox won big, they didn’t do it quietly. They scored seven runs in Game 2, then erupted for eight runs in each of Games 5 and 6 — numbers that felt borderline scandalous in a dead-ball World Series. These were not bloop-and-a-prayer victories. They were thumpings.

The Chicago Tribune remarked that Charles Comiskey’s “hitless wonders suddenly developed a batting streak which carried them to victory in spite of everything,” noting that Cubs pitchers who had bottled them up earlier were “driven to the woods inside of five innings.” Other papers joined in. The Inter-Ocean reported that the “so-called hitless wonders got busy,” unleashing a “tremendous batting clip” that sent Cubs ace Three-Finger Brown to the showers.

After one lopsided victory, the Inter-Ocean went further, writing that the White Sox were “wielding the big stick with Rooseveltian vigor.” These were not men surviving on guile alone; they were, at least for a few October afternoons, swinging freely and without apology. Even Charles Comiskey leaned into the irony. After Game 5, he told reporters, “If the hitless wonders do not hit any better tomorrow than they did today, they will win the world’s championship without playing the seventh game.”

Individual performances backed it up. George Davis and Jiggs Donahue never hit home runs, but in the Series they produced like stars — Donahue posting an OPS of .909 and Davis .846 — strong numbers for any era, let alone one played with a soggy ball and a cavernous outfield. By the time the final out settled into a glove, Chicago’s papers had reached a quiet consensus. The White Sox may have arrived in October as the "hitless wonders,” but they did not leave it that way.

Truth-O-Meter Verdict

So were the 1906 White Sox really “hitless wonders”?

Our AI Truth-O-Meter weighs reputation against results, separating baseball shorthand from baseball reality. Its verdict — The hitless wonders nickname might be technically true (they didn't get a lot of hits) but it is certainly misleading. This was a good offense. Judged by what actually wins baseball games — scoring runs — they were comfortably above average, elite at drawing walks, nearly impossible to strike out, good at wearing down starting pitchers, and ruthlessly efficient at turning contact into offense.

Advance Scout Report — Chicago White Sox Offense (1906)

For this story, we had our AI step into the role of a 1906 advance scout — not to rewrite history, but to reinterpret it. Using modern sabermetric concepts like on-base value, strikeout avoidance, and run creation, the AI analyzes the White Sox as if it were preparing the Chicago Cubs for the World Series with today’s analytical tools. The language is period-appropriate, but the evaluation is modern: an attempt to translate a dead-ball offense into terms a contemporary front office would recognize.

Filed for Chicago Cubs coaching staff:

Do not be misled by the nickname. This club does not hit often, but it hits enough, and it refuses to give pitchers easy innings. Finished last in the league in total hits and near the bottom in power with just seven home runs, yet still scored 567 runs — sixth out of fourteen clubs. They manufacture offense through patience and contact. Team on-base percentage sits at .301 in a league that does not value walks on the scoreboard but rewards them on the field. They draw 453 walks, most in the American League, and strike out only 492 times — fewest in the league. They make you earn every out.

This lineup is built to exhaust starting pitching. Against right-handers they went 71–39, and it shows in approach: long at-bats, foul balls, and runners constantly in motion. They do not chase early. Pitch counts rise. Defensive pressure follows. One walk turns into a run before you realize the inning is in trouble.

Jiggs Donahue is the steadiest presence in the order. Limited power, but strong on-base skill for the era and one of the club’s best at avoiding strikeouts. He shortens his swing with men on base and is content to keep the line moving rather than force damage. George Davis, though past his prime, remains the most complete offensive player on the roster, with above-average on-base ability, solid gap power for the period, and excellent situational awareness. Neither man is a home-run threat, but both convert opportunities at a higher rate than the raw hit totals suggest.

Frank Isbell sets the tone. High contact, above-average on-base numbers, and enough speed to force hurried throws. Fielder Jones does not hit for average but draws walks at an elite rate and will not expand the zone. Ed Hahn and John O’Neill fit the same profile — limited damage, but persistent. This club strings together plate appearances rather than hits.

Summary for the pitching staff: do not expect them to beat themselves. Strikeouts are rare. Fast innings are unlikely. If you pitch for contact, you must locate. If you pitch for power, you will fall behind in the count. They look hitless. They are not harmless.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

A little AI make-believe: The 1906 Cubs write up a report on the "Hitless Wonders." (below)

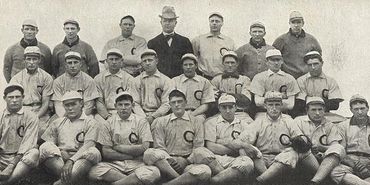

The 1906 Chicago White Sox including George Davis (left), Jiggs Donahue (Right) and Charles Comiskey.

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.