Gone Baby Gone: Stealing Home

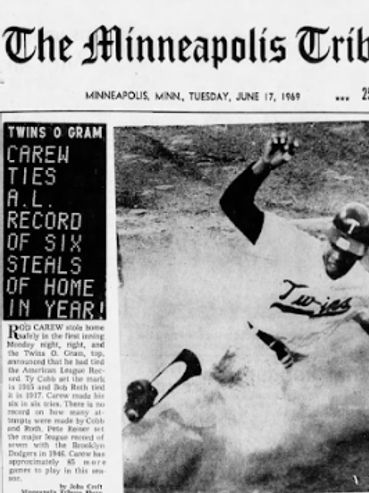

Rod Carew Steals Home

Part I — Deadball Dare Devils

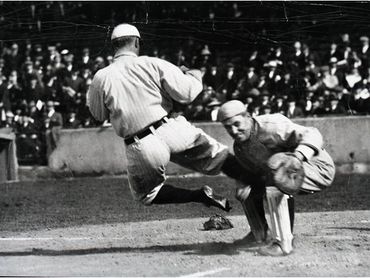

Once upon a time, stealing home wasn’t an act of madness — it was an art form. In the early decades of the 20th century, basepaths were crowded with daredevils who saw third base not as a stopping point, but as a launch pad. Ty Cobb, ever the snarling showman, stole home 54 times, a record so untouchable it feels like mythology.

Even Babe Ruth, no one’s idea of a speedster, swiped home 10 times in his career — proof that guts, not legs, were the real currency of the era. Back then, the game’s pulse was quickened by players who treated ninety feet like a dare.

Through the 1930s and ’40s, the move remained a high-wire thrill act. Brooklyn’s Pete Reiser once stole home seven times in a single season, and Jackie Robinson’s electrifying dash in the 1955 World Series became a touchstone moment — the snapshot of pure nerve that every kid reenacted in a sandlot. For decades, the steal of home was baseball’s heartbeat — half-reckless, half-genius.

But by the 1960s, that heartbeat was fading. Pitchers had learned the slide-step. Catchers had learned to cheat toward the plate. Managers had learned that giving away an out was statistical suicide. The great base thieves of the modern era — Henderson, Raines, even Wills — could rack up triple-digit steals while rarely daring that final, suicidal sprint.

And yet, in the summer of 1969, one man brought it back from extinction — not as a gimmick, but as a weapon. His name was Rod Carew.

Part II — The Summer of Stealing Home

Perhaps the most daring stretch of base-running in modern baseball came in the summer of 1969, when Rod Carew — the quiet, smooth Minnesota Twins second baseman stole home seven times in one season.

This wasn’t the Deadball Era, and it wasn’t desperation baseball. Carew wasn’t supposed to be doing this — and yet there he was, tip-toeing down the line, studying pitchers’ legs like a chess player timing a gambit. Even his manager Billy Martin couldn’t resist the audacity. “He’s got the green light anytime he wants now,” Martin told reporters after one early steal, though he admitted he had “spoken to him about it.” Carew, typically understated, said he didn’t plan to try it “under those circumstances” again — and then, of course, did it anyway.

From the beginning, he was analyzing every detail. After an April steal against the Angels, Carew recalled: “Billy gave me the signal to go. I didn’t get a good jump, but when Hoyt Wilhelm went into his slow windup, I knew there wasn’t any way he was going to get me at home. I was across the plate before the ball got there.” Later that season, he explained that most pitchers had learned their lesson — nearly all worked from the stretch with him on third — but when one left-hander in Chicago absent-mindedly went into a windup, “I took advantage of it. I doubt that I’ll see another windup the rest of the year.” He added that he hadn’t stolen home at all the previous year — “but I did steal four in the minors, so it’s something I’ve worked on.”

Opposing managers hated it. California’s Lefty Phillips called one first-inning steal a “showboating stunt,” complaining that “stunts like that might cost his club the pennant.” The remark said as much about baseball’s culture as it did about Carew: quiet players were supposed to stay in their lanes, not humiliate young pitchers.

Even Detroit’s Mickey Lolich, no stranger to pressure, sounded half-offended after Carew and César Tovar pulled a double steal of home in May. “Anytime a team has to try to steal bases, or bunt, or drag the ball to score,” Lolich said, “they’re admitting they can’t hit.” Then, almost grudgingly, he added, “I was especially watchful when Tovar and Carew stole home. This is something I’ll have to watch in the future.”

The hostility reached its comic peak a few weeks later when Ted Williams of Washington promised to fine any of his pitchers $50 if they ever allowed Carew to steal home again. After a near-beanball retaliation threat, Martin reportedly barked back, “If you do, we’ll get you up there and stick one in your fat belly.”

By then Carew’s reputation had gone from smooth to swaggering. Yet he remained as composed as ever — “I guess I took another RBI away from Harmon,” he joked after one successful swipe. “Maybe I can score from first on a single next time.”

The most complete account came from the Yankees series in June, when Carew got a special steal-sign from Martin, dashed for the plate, and later shrugged, “I didn’t think the play at home was especially close.” The opposing catcher, John Ellis, was blunter: “He might have run them right out of the inning.”

By mid-July, Carew had stolen home for the seventh and final time that season, tying Pete Reiser’s 1946 major-league record. Afterward he told reporters, “I’m very, very happy. What else can you say? To me, it’s more of a thrill to steal home than to hit one out.” All seven of his steals came before August — a stunning burst of audacity compressed into barely three months.

Part III — The Math of Madness

On June 16, 1969, Rod Carew pulled off one of the strangest steals of his remarkable season. With nobody out in the first inning, Harmon Killebrew — Minnesota’s best power hitter — stood at the plate, and runners occupied second and third. It was the very definition of a “don’t-run” situation. Yet Carew broke for home anyway and slid in safely before catcher Joe Azcue could even tag him.

Afterward, manager Billy Martin was equal parts awed and annoyed. “It’s not a good idea to take a gamble at a time like that,” he told reporters, pointing out that with Killebrew batting, the Twins didn’t exactly need to manufacture a run. Carew simply smiled and said he got such a good jump that he knew he could make it.

Moments like that highlight the paradox of Carew’s 1969 spree: breathtaking instinct married to statistical recklessness. So we asked our AI Skipper to evaluate the logic behind a steal of home — then and now — using modern run-expectancy data.

The AI’s verdict was blunt: for a steal of home to make sense, the success rate must exceed roughly 85 percent when there are two outs, and closer to 90 percent with none out. In the scenario Carew chose — nobody out, runners on second and third, and a Hall of Fame slugger batting — even a 95 percent success rate barely breaks even. The expected value of staying put is simply too high.

That’s why in today’s game, the steal of home has become almost extinct. The AI Skipper estimates that across the modern era, the league-wide success rate for attempted steals of home hovers around 26 percent — a figure that makes managers reach for the antacids. Only in very specific contexts — two outs, a weak hitter at the plate, or maybe a left-handed who is completely napping — does the math make any sense at all.

And yet, what made Carew’s seven steals so memorable is that he did it anyway. His success rate wasn’t logical; it was transcendental. In 1969, he was 7-for-7 — a statistical impossibility by today’s standards. The AI Skipper concluded that “even if every other variable were ideal, the odds of such perfection are less than one in a thousand.”

Which is to say, Rod Carew didn’t just steal home — he stole probability itself.

— AI Baseball Guy | Human perspective. AI precision. Baseball reimagined.

Our AI Skipper doesn't like the odds on stealing home.

Rod Carew, Jackie Robinson, and Ty Cobb steal home.

More from AI Baseball Guy

Connect With Us

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.